- Home

- Tara Moore

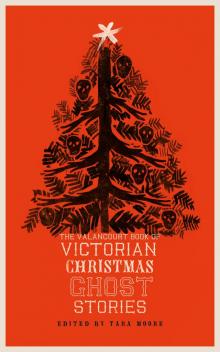

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Page 8

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Read online

Page 8

There was now no light left, though the red cinders yet glowed with a ruddy gleam, like the eyes of wild beasts. The chain rattled no more. I tried to speak, to scream wildly for help; my mouth was parched, my tongue refused to obey. I could not utter a cry, and, indeed, who could have heard me, alone as I was in that solitary chamber, with no living neighbour, and the picture-gallery between me and any aid that even the loudest, most piercing shriek could summon. And the storm that howled without would have drowned my voice, even if help had been at hand. To call aloud—to demand who was there—alas! how useless, how perilous! If the intruder were a robber, my outcries would but goad him to fury; but what robber would act thus? As for a trick, that seemed impossible. And yet, what lay by my side, now wholly unseen? I strove to pray aloud, as there rushed on my memory a flood of weird legends—the dreaded yet fascinating lore of my childhood. I had heard and read of the spirits of wicked men forced to revisit the scenes of their earthly crimes—of demons that lurked in certain accursed spots—of the ghoul and vampire of the East, stealing amid the graves they rifled for their ghostly banquets; and I shuddered as I gazed on the blank darkness where I knew it lay. It stirred—it moaned hoarsely; and again I heard the chain clank close beside me—so close that it must almost have touched me. I drew myself from it, shrinking away in loathing and terror of the evil thing—what, I knew not, but felt that something malignant was near. And yet, in the extremity of my fear, I dared not speak; I was strangely cautious to be silent, even in moving farther off; for I had a wild hope that it—the phantom, the creature, whichever it was—had not discovered my presence in the room. And then I remembered all the events of the night—Lady Speldhurst’s ill-omened vaticinations, her half-warnings, her singular look as we parted, my sister’s persuasions, my terror in the gallery, the remark that “this was the room nurse Sherrard used to talk of.” And then memory, stimulated by fear, recalled the long forgotten past, the ill-repute of this disused chamber, the sins it had witnessed, the blood spilled, the poison administered by unnatural hate within its walls, and the tradition which called it haunted. The green room—I remembered now how fearfully the servants avoided it—how it was mentioned rarely, and in whispers, when we were children, and how we had regarded it as a mysterious region, unfit for mortal habitation. Was It—the dark form with the chain—a creature of this world, or a spectre? And again—more dreadful still—could it be that the corpses of wicked men were forced to rise, and haunt in the body the places where they had wrought their evil deeds? And was such as these my grisly neighbour?

The chain faintly rattled. My hair bristled; my eyeballs seemed starting from their sockets; the damps of a great anguish were on my brow. My heart laboured as if I were crushed beneath some vast weight. Sometimes it appeared to stop its frenzied beatings, sometimes its pulsations were fierce and hurried; my breath came short and with extreme difficulty, and I shivered as if with cold; yet I feared to stir. It moved, it moaned, its fetters clanked dismally, the couch creaked and shook. This was no phantom, then—no air-drawn spectre. But its very solidity, its palpable presence, were a thousand times more terrible. I felt that I was in the very grasp of what could not only affright, but harm; of something whose contact sickened the soul with deathly fear. I made a desperate resolve: I glided from the bed, I seized a warm wrapper, threw it around me, and tried to grope, with extended hands, my way to the door. My heart beat high at the hope of escape.

But I had scarcely taken one step, before the moaning was renewed, it changed into a threatening growl that would have suited a wolf’s throat, and a hand clutched at my sleeve. I stood motionless. The muttering growl sank to a moan again, the chain sounded no more, but still the hand held its gripe of my garment, and I feared to move. It knew of my presence, then. My brain reeled, the blood boiled in my ears, and my knees lost all strength, while my heart panted like that of a deer in the wolf’s jaws. I sank back, and the benumbing influence of excessive terror reduced me to a state of stupor.

When my full consciousness returned, I was sitting on the edge of the bed, shivering with cold, and barefooted. All was silent, but I felt that my sleeve was still clutched by my unearthly visitant. The silence lasted a long time. Then followed a chuckling laugh, that froze my very marrow, and the gnashing of teeth as in demoniac frenzy; and then a wailing moan, and this was succeeded by silence. Hours may have passed—nay, though the tumult of my own heart prevented my hearing the clock strike, must have passed—but they seemed ages to me. And how were they spent? Hideous visions passed before the aching eyes that I dared not close, but which gazed ever into the dumb darkness where It lay—my dread companion through the watches of the night. I pictured It in every abhorrent form which an excited fancy could summon up: now as a skeleton, with hollow eyeholes and grinning fleshless jaws; now as a vampire, with livid face and bloated form, and dripping mouth wet with blood. Would it never be light! And yet, when day should dawn, I should be forced to see It face to face. I had heard that spectre and fiend were compelled to fade as morning brightened, but this creature was too real, too foul a thing of earth, to vanish at cockcrow. No! I should see it—the horror—face to face! And then the cold prevailed, and my teeth chattered, and shiverings ran through me, and yet there was the damp of agony on my bursting brow. Some instinct made me snatch at a shawl or cloak that lay on a chair within reach, and wrap it round me. The moan was renewed, and the chain just stirred. Then I sank into apathy, like an Indian at the stake, in the intervals of torture.

Hours fled by, and I remained like a statue of ice, rigid and mute. I even slept, for I remember that I started to find the cold grey light of an early winter’s day was on my face, and stealing around the room from between the heavy curtains of the window. Shuddering, but urged by the impulse that rivets the gaze of the bird upon the snake, I turned to see the Horror of the night. Yes, it was no fevered dream, no hallucination of sickness, no airy phantom unable to face the dawn. In the sickly light I saw it lying on the bed, with its grim head on the pillow. A man? Or a corpse arisen from its unhallowed grave, and awaiting the demon that animated it? There it lay—a gaunt gigantic form, wasted to a skeleton, half clad, foul with dust and clotted gore, its huge limbs flung upon the couch as if at random, its shaggy hair streaming over the pillows like a lion’s mane. Its face was towards me. Oh, the wild hideousness of that face, even in sleep! In features it was human, even through its horrid mask of mud and half-dried bloody gouts, but the expression was brutish and savagely fierce; the white teeth were visible between the parted lips, in a malignant grin; the tangled hair and beard were mixed in leonine confusion, and there were scars disfiguring the brow. Round the creature’s waist was a ring of iron, to which was attached a heavy but broken chain—the chain I had heard clanking. With a second glance I noted that part of the chain was wrapped in straw, to prevent its galling the wearer. The creature—I cannot call it a man—had the marks of fetters on its wrists, the bony arm that protruded through one tattered sleeve was scarred and bruised; the feet were bare, and lacerated by pebbles and briers, and one of them was wounded, and wrapped in a morsel of rag. And the lean hands, one of which held my sleeve, were armed with talons like an eagle’s. In an instant the horrid truth flashed upon me—I was in the grasp of a madman. Better the phantom that scares the sight than the wild beast that rends and tears the quivering flesh—the pitiless human brute that has no heart to be softened, no reason at whose bar to plead, no compassion, nought of man save the form and the cunning. I gasped in terror. Ah! the mystery of those ensanguined fingers, those gory wolfish jaws! that face, all besmeared with blackening blood, is revealed!

The slain sheep, so mangled and rent—the fantastic butchery—the print of the naked foot—all, all were explained; and the chain, the broken link of which was found near the slaughtered animals—it came from his broken chain—the chain he had snapped, doubtless, in his escape from the asylum where his raging frenzy had been fettered and bound. In vain! in vain! Ah, me! how had this g

risly Samson broken manacles and prison bars—how had he eluded guardian and keeper and a hostile world, and come hither on his wild way, hunted like a beast of prey, and snatching his hideous banquet like a beast of prey, too? Yes, through the tatters of his mean and ragged garb I could see the marks of the severities, cruel and foolish, with which men in that time tried to tame the might of madness. The scourge—its marks were there; and the scars of the hard iron fetters, and many a cicatrice and welt, that told a dismal tale of harsh usage.

But now he was loose, free to play the brute—the baited, tortured brute that they had made him—now without the cage, and ready to gloat over the victims his strength should overpower. Horror! horror! I was the prey—the victim—already in the tiger’s clutch; and a deadly sickness came over me, and the iron entered into my soul, and I longed to scream, and was dumb! I died a thousand deaths as that awful morning wore on. I dared not faint. But words cannot paint what I suffered as I waited—waited till the moment when he should open his eyes and be aware of my presence; for I was assured he knew it not. He had entered the chamber as a lair, when weary and gorged with his horrid orgie; and he had flung himself down to sleep without a suspicion that he was not alone. Even his grasping my sleeve was doubtless an act done betwixt sleeping and waking, like his unconscious moans and laughter, in some frightful dream.

Hours went on; then I trembled as I thought that soon the house would be astir, that my maid would come to call me as usual, and awake that ghastly sleeper. And might he not have time to tear me, as he tore the sheep, before any aid could arrive? At last what I dreaded came to pass—a light footstep on the landing—there is a tap at the door. A pause succeeds, and then the tapping is renewed, and this time more loudly. Then the madman stretched his limbs and uttered his moaning cry, and his eyes slowly opened—very slowly opened, and met mine. The girl waited awhile ere she knocked for the third time. I trembled lest she should open the door unbidden—see that grim thing, and by her idle screams and terror bring about the worst. Long before strong men could arrive I knew that I should be dead—and what a death!

The maid waited, no doubt surprised at my unusually sound slumbers, for I was in general a light sleeper and an early riser, but reluctant to deviate from habit by entering without permission. I was still alone with the thing in man’s shape, but he was awake now. I saw the wondering surprise in his haggard bloodshot eyes; I saw him stare at me half vacantly, then with a crafty yet wondering look; and then I saw the devil of murder begin to peep forth from those hideous eyes, and the lips to part as in a sneer, and the wolfish teeth to bare themselves. But I was not what I had been. Fear gave me a new and a desperate composure—a courage foreign to my nature. I had heard of the best method of managing the insane; I could but try; I did try. Calmly, wondering at my own feigned calm, I fronted the glare of those terrible eyes. Steady and undaunted was my gaze—motionless my attitude. I marvelled at myself, but in that agony of sickening terror I was outwardly firm. They sink, they quail abashed, those dreadful eyes, before the gaze of a helpless girl; and the shame that is never absent from insanity bears down the pride of strength, the bloody cravings of the wild beast. The lunatic moaned and drooped his shaggy head between his gaunt squalid hands. I lost not an instant. I rose, and with one spring reached the door, tore it open, and, with a shriek, rushed through, caught the wondering girl by the arm, and, crying to her to run for her life, rushed like the wind along the gallery, down the corridor, down the stairs. Mary’s screams filled the house as she fled beside me. I heard a long-drawn, raging cry, the roar of a wild animal mocked of its prey, and I knew what was behind me. I never turned my head—I flew rather than ran. I was in the hall already; there was a rush of many feet, an outcry of many voices, a sound of scuffling feet, and brutal yells, and oaths, and heavy blows, and I fell to the ground, crying, “Save me!” and lay in a swoon.

I awoke from a delirious trance. Kind faces were around my bed, loving looks were bent on me by all, by my dear father and dear sisters, but I scarcely saw them before I swooned again. . . .

When I recovered from that long illness, through which I had been nursed so tenderly, the pitying looks I met made me tremble. I asked for a looking-glass. It was long denied me, but my importunity prevailed at last—a mirror was brought. My youth was gone at one fell swoop. The glass showed me a livid and haggard face, blanched and bloodless as of one who sees a spectre; and in the ashen lips, and wrinkled brow, and dim eyes, I could trace nothing of my old self. The hair, too, jetty and rich before, was now as white as snow, and in one night the ravages of half a century had passed over my face. Nor have my nerves ever recovered their tone after that dire shock. Can you wonder that my life was blighted, that my lover shrank from me, so sad a wreck was I?

I am old now—old and alone. My sisters would have had me to live with them, but I chose not to sadden their genial homes with my phantom face and dead eyes. Reginald married another. He has been dead many years. I never ceased to pray for him, though he left me when I was bereft of all. The sad weird is nearly over now. I am old, and near the end, and wishful for it. I have not been bitter or hard, but I cannot bear to see many people, and am best alone. I try to do what good I can with the worthless wealth Lady Speldhurst left me, for at my wish my portion was shared between my sisters. What need had I of inheritances?—I, the shattered wreck made by that one night of horror!

“BRING ME A LIGHT!”

A GHOST STORY

Once a Week (1859-1880), the periodical in which this story first appeared in January 1861, originated from a dispute over celebrity publicity. Publishers Bradbury and Evans refused to print Charles Dickens’s defense of his marital separation, and their successful joint endeavor Household Words was the casualty. Bradbury and Evans found a new editor and started Once a Week, which became an outlet for Punch writers and illustrators.2 This story appeared during the magazine’s most successful period.

This story plays on the realistic nineteenth-century fear of death by fire. Between 1848 and 1861, nearly 40,000 people in England were burned alive or scalded to death; after the breeching age of five, girls were 60% more susceptible to this end than boys due to their flammable clothing; the danger was also higher for older women.3 Authorities recommended that Victorians starch cotton, linen, and muslin dresses with fire-resistant chemicals to avoid this danger.

2 John Sutherland, “Once a Week” in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1989. 479-480.

3 “Death by Fire—In the 14 Years 1848-61.” The Times (London) 24537 (20 April 1863): 5.

My name is Thomas Whinmore, and when I was a young man I went to spend a college vacation with a gentleman in Westmoreland. He had known my father’s family, and had been appointed the trustee of a small estate left me by my great aunt, Lady Jane Whinmore. At the time I speak of I was one-and-twenty, and he was anxious to give up the property into my hands. I accepted his invitation to “come down to the old place and look about me.” When I arrived at the nearest point to the said “old place,” to which the Carlisle coach would carry me, I and my portmanteau were put into a little cart, which was the only wheeled thing I could get at the little way-side inn.

“How far is it to Whinmore?” I asked of a tall grave-looking lad, who had already informed me I could have “t’horse and cairt” for a shilling a mile.

“Twal mile to t’ould Hall gaet—a mile ayont that to Squire Erle’s farm.”

As I looked at the shaggy wild horse, just caught from the moor for the purpose of drawing “t’cairt,” I felt doubtful as to which of us would be the master on the road. I had ascertained that the said road lay over moor and mountain—just the sort of ground on which such a steed would gambol away at his own sweet will. I had no desire to be run away with.

“Is there any one here who can drive me to Mr. Erle’s?” I asked of the tall grave lad.

“Nobbut fayther.”

I was puzzled; and was about to ask for an explan

ation, when a tall, strong old man, as like the young one as might be, came out from the door of the house with his hat on, and a whip in his hand. He got up into the cart, and looking at me, said,

“Ye munna stan here, sir. We shan’t pass Whinmore Hall afore t’deevil brings a light.”

“But I want something to eat before we start,” I remonstrated. “I’ve had no dinner.”

“Then ye maun keep your appetite till supper time,” replied the old man. “I canna gae past Whinmore lights for na man—nor t’horse neither. Get up wi’ ye! Joe, lend t’gentleman a hand.”

Joe did as he was desired, and then said—

“Will ye be home the night, fayther?”

“May be yees, may be na, lad; take care of t’place.”

In a moment the horse started, and we were rattling over the moor at the rate of eight miles an hour. Surprise, indignation, and hunger possessed me. Was it possible I had been whirled off dinnerless into this wilderness against my own desire?

“I say, my good man,” I began.

“My name is Ralph Thirlston.”

“Well! Mr. Thirlston, I want something to eat. Is there any inn between this desert and Mr. Erle’s house!”

“Nobbut Whinmore Hall,” said the old man, with a grin.

“I suppose I can get something to eat there, without being obliged to anybody. It is my own property.”

Mr. Thirlston glanced at me sharply.

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories

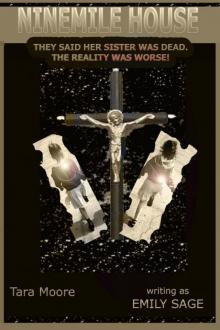

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Ninemile House

Ninemile House