- Home

- Tara Moore

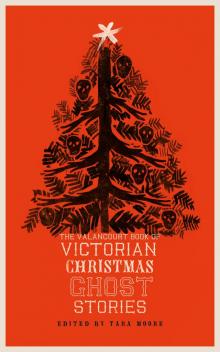

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Read online

THE VALANCOURT BOOK OF

VICTORIAN CHRISTMAS

GHOST STORIES

Edited with an introduction by

TARA MOORE

VALANCOURT BOOKS

Richmond, Virginia

2016

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories

First published December 2016

Introduction © 2016 by Tara Moore

This compilation copyright © 2016 by Valancourt Books, LLC

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the copying, scanning, uploading, and/or electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitutes unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher.

Published by Valancourt Books, Richmond, Virginia

http://www.valancourtbooks.com

Cover by Henry Petrides

INTRODUCTION

How to Read a Victorian Christmas Ghost Story

Imagine a midwinter night, an early sunset, a long, drafty evening spent by candlelight. The season of Christmas coincides with the shortest days of the year and, for middle-class Victorians, a chance for families to reconnect in story-telling circles. Urban dwellers, disconnected from village legends, simply picked up a magazine specially made to lace children’s dreams with terror. The bleak, shadow-filled walk from the story circle to one’s dark bedroom presented an uncomfortably eerie space to reflect on the mental images conveyed by those grisly tales.

To capture the Victorian ghost story experience is to whisper it by candlelight, to feel the tendrils of December’s chill reaching from the darkness outside the hearth’s glow. While our culture associates the summer campfire with this type of tale, the Victorians looked to Christmas fires instead. Walter Scott, at the opening of his ghostly tale “The Tapestried Chamber,” bemoans how his written words will strip the story of its most satisfying chills. Read it aloud, he urges his readers. Read it at night.

The History of Ghosts at Christmas

Ghosts had been a staple of both periodicals and Christmas for a century before the Victorian Christmas publishing boom, but the nineteenth century offered as a nexus for these two cultural icons. Eighteenth-century periodicals concerned with enlightenment had recognized that “ghosts were a problem to be solved” (Handley 113). While these periodical essays did confer a level of distinction on ghosts, they failed to fully harness the Christmas reading experience. When taxation on periodicals raised prices and circulations dropped, ghosts resorted to starring in oral accounts. The midwinter tradition of telling ghostly tales around the long evening fire satisfied both the poor and the rich. This tradition became entrenched in the printed accounts of Christmas. For example, when Washington Irving sought to capture the dignified glamour of the English country Christmas for his readers in 1820, he included the comfortable thrill of the ghost story circle as well as the boar’s head and the wassail bowl.

The first literary genre to capitalize on this oral tradition, the Christmas literary annual, became especially popular in the 1820s and 1830s. Dozens of titles popped up to fill the desire of middle-class Victorians to present or display these lushly illustrated, gilded volumes. The gothic ghost story commonly featured in the table of contents of these decorative books. Literary annuals predated the mid-century Christmas book trend, but they further established the place of the ghost story in printed reading matter intended for Christmas use (Moore 81-82). By 1843, a young author would grasp at this genre when he needed some extra cash.

Charles Dickens did not invent the Victorian Christmas, but he did come to represent its commercial potential for publishing profit. Of his five small Christmas novellas, two contained outright ghosts, and another hinged on a supernatural scene. When Dickens found the work of publishing an annual Christmas book too exhausting (and not as profitable as he could have wished), he turned to preparing frame tales populated by the stories of some of the most popular writers of his day. These appeared as special Christmas numbers in the weekly magazines he edited: Household Words and, later, All the Year Round. Other magazines would follow suit, most of them soliciting authors to contribute ghost stories to add to the mix.

The real wellspring of Victorian Christmas spectres was the magazine. Periodicals began printing special Christmas numbers or simply tailoring their December and January numbers for Christmas reading, and that meant ghosts. Women contributed a large portion of these stories, and scholars have estimated that perhaps between fifty and seventy percent of all ghost fiction from the nineteenth century was written by women (Carpenter and Kolmar xvi). Readers wanted to read ghosts at Christmas, so that meant that authors dreamed up midwinter ghosts over the summer and into the early fall, preparing the way for those spooky holiday chills.

Why Did the Victorians Love Ghost Stories?

Cultural elements contributed to the success of this transformed oral tradition. Authors who wrote about ghosts could have easily participated in the fad for séances that pervaded certain spheres of society. Nineteenth-century spiritualism shaped “a language of spectrality” which then influenced the production of ghosts in literature (Smith 97). Victorians, who enjoyed increasing levels of leisure and technology, devoted a portion of each to developing a robust culture of death and mourning, including photography of deceased children and picnicking in cemeteries (Carpenter and Kolmar xix). With their fascination with death and the afterlife, the Victorians appreciated when literature roamed into the realm of the uncanny. The following ghostly selections represent the style of ghost stories the Victorians could expect to find in the pages of their periodicals.

Most Victorian ghosts fail to provide the fright that modern audiences have come to expect. Horror fiction and films have no doubt desensitized us to the simple thrill of local ghost lore. The Victorians themselves were dealing with a debate over spiritualism and spirits which severely limited their ability to fully enjoy the ghostly horror story. Authors frequently wrote cautionary anti-ghost stories, the type that open with a sinister suggestion of a ghost, only to end with characters recognizing the foolishness of such a fear. For example, the bang in the night that caused the young bride to panic for five pages ends up being the fallen kitchen clock (“The Mystery”). Dickens used the pages of his periodicals to question the premise that ghosts had any basis in fact (Smajic 60). Disgusted with his culture’s belief in ghosts, Dickens produced an entirely ghost-less Christmas number, The Haunted House (1859), in which a party of friends collect in a so-called haunted house to experience its thrill or demystify its reputation.

This volume gives preference to the eerier tales from the period, but several included here do hinge on an entirely rational explanation. It is as if authors knew that their readers demanded ghost stories, but the same authors simply could not bring themselves to further confirm the reality of ghosts. Looking back on the late-nineteenth-century ghost trend, one critic wrote, “story-writers found it as much as their place was worth to introduce any element of the apparently supernatural which was not capable of a severely practical explanation” (Berlyn). One story contained here, “How Peter Parley Laid a Ghost: A Story of Owl’s Abbey,” takes a highly didactic tone. Since Peter Parley’s Annual was entrusted with teaching Victorian children the realities of their world, readers could be certain from the outset that the tease of a ghost would end with a very human lesson.

Several trends in Victorian ghost narratives rest on the premise that ghosts ar

e real, at least in fiction. The emigrant’s return is one such variety. In this brand of tale, the émigré’s form appears to his lover or friend, typically at the moment of his death. These spectral visitants are nearly always male, and their appearance signifies their deep devotion to home and place of origin, no matter where in the Empire they have sought their fortune. In one tale, a press gang kidnaps a young man and drags him off to work on a navy vessel; his ghost appears to his fiancée three years later, conveying to her the instantaneous knowledge of his death (Sheehan). While this type of tale appeared throughout the year, the strong sentimentality regarding Christmas family unity made it especially fitting for holiday reading; at that time of the year, families of émigrés would have wanted to feel that they were still the focal point in the lives of their distant loved ones.

Another type of real ghost story involved “laying the ghost,” a British phrase for releasing the ghost from whatever past crimes force it to roam the earth. Sometimes the ghost’s crimes bind it to this plane, but, more often, the ghost wishes to help its relatives establish financial stability or peace. The ghost may continue to haunt until a particular wrong is righted, and then it is free to drift away. Several of the stories contained here deal with laying the ghost, either by solving a mystery or establishing financial security for the living.

While working-class ghosts rarely haunt anyone over a will, the spectres of the gentry carry the burden of seeing that their bequests are carried out. This otherworldly responsibility plays out in many country house hauntings, a subgenre well represented in this anthology. While working-class ghosts could be found in Victorian periodicals, their wealthier counterparts certainly received more attention. Indeed, readers seemed to idealize the country house Christmas, even though more and more readers celebrated the holiday in an urban setting, and few could boast of such a leisured lifestyle (Moore 89). Perhaps the idea of a haunted estate satisfied the voyeuristic middle class; after all, a haunting is certainly a disruption of a seemingly stable environment (Wolfreys 6). The ghost story offers readers a chance to fantasize about the destabilization of the powerful. Periodical readers could partake in this pastime by picking up their Christmas annual without ever having to leave town.

In his 1884 essay, “The Decay of the British Ghost,” F. Anstey sardonically bemoans the loss of the real ghost: “There was something thoroughly Christmassy, for example, about the witchlike old lady, with a horrible dead rouged face, who looked out of a tarnished mirror and gibbered malevolently at somebody, for the excellent reason that he chanced to be her descendant” (252). Anstey’s ironic assessment of the state of the ghost rings false in one way; ghosts certainly survived the mid-century boom and continued to feature during the last decades of the century and beyond. However, the ghost story did serve as a type of uncanny mirror, often showing subtle fissures in the society that produced it.

To revive the Victorian ghost, invite it in on its own terms. Wait for dark. Dim the lights. If you can arrange a draft to waft through the room, all the better. Meeting the ghosts of Christmas does not limit you to Dickens’s edifying spirits; instead, prepare yourself for a sensual experience of midwinter leisure and Victorian story-telling tradition.

Tara Moore

May 2016

Tara Moore celebrates Christmas in central Pennsylvania where the whip-bearing, fur-clad Belsnickle still terrifies the children who know where to find him. Her publications include articles and books about Christmas, including Victorian Christmas in Print (2009) and Christmas: The Sacred to Santa (2014). She teaches writing and literature at Elizabethtown College.

Works Cited

Anstey, F. “The Decay of the British Ghost,” Longman’s Magazine 3.145 (1 Jan. 1884): 251-259. Periodicals Archive Online. 9 April 2016. Web.

Berlyn, Alfred. “Ghosts Up-to-date,” The Academy 2172 (20 Dec. 1913): 774-775.

Carpenter, Lynette and Wendy Kolmar. Ghost Stories by British and American Women: A Selected, Annotated Bibliography. New York: Garland, 1998.

Dickens, Charles, ed., The Haunted House. New York: Modern Library, 2004.

Handley, Sasha. Visions of an Unseen World: Ghost Beliefs and Ghost Stories in Eighteenth-Century England. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2007.

Irving, Washington. The Sketch-book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. [1820]. New York: Library of America, 1983.

Moore, Tara. Victorian Christmas in Print. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

“The Mystery of the Old Grey House,” Tinsley’s Magazine 36 (Jan. 1885): 168-178.

Scott, Walter. “The Tapestried Chamber; or, The Lady in the Sacque,” The Keepsake for 1829. London: Hurst, Chance & Co., 1828.

Smajic, Srdjan. Ghost-Seers, Detectives and Spiritualists: Theories of Vision in Victorian Literature and Science. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Sheehan, John. “A Ghostly Night at Ballyslaughter” Temple Bar 31 (January 1871): 227-236.

Smith, Andrew. The Ghost Story, 1840-1920: A Cultural History. New York: Manchester University Press, 2010.

Wolfreys, Julian. Victorian Hauntings: Spectrality, Gothic, the Uncanny and Literature. New York: Palgrave, 2002.

Sir Walter Scott

THE TAPESTRIED CHAMBER

Testing out haunted houses featured frequently in ghost stories, but usually the brave soul made the decision willingly, either out of a desire to disprove spiritualism or to simply enjoy a thrill. With the creation of General Browne, an American War campaigner, Walter Scott (1771-1832) describes a hearty, masculine character who also has access to an elegant country house. In this tale, General Browne returns from war only to face a trial for which his hardships in the Virginian wilds have not prepared him. This story first appeared in 1828 in The Keepsake, a literary annual that appeared at Christmas each year from 1828 to 1857.

The following narrative is given from the pen, so far as memory permits, in the same character in which it was presented to the author’s ear; nor has he claim to further praise, or to be more deeply censured, than in proportion to the good or bad judgment which he has employed in selecting his materials, as he has studiously avoided any attempt at ornament which might interfere with the simplicity of the tale.

At the same time it must be admitted, that the particular class of stories which turns on the marvellous, possesses a stronger influence when told, than when committed to print. The volume taken up at noonday, though rehearsing the same incidents, conveys a much more feeble impression, than is achieved by the voice of the speaker on a circle of fire-side auditors, who hang upon the narrative as the narrator details the minute incidents which serve to give it authenticity, and lowers his voice with an affectation of mystery while he approaches the fearful and wonderful part. It was with such advantages that the present writer heard the following events related, more than twenty years since, by the celebrated Miss Seward, of Lichfield, who, to her numerous accomplishments, added, in a remarkable degree, the power of narrative in private conversation. In its present form the tale must necessarily lose all the interest which was attached to it, by the flexible voice and intelligent features of the gifted narrator. Yet still, read aloud, to an undoubting audience by the doubtful light of the closing evening, or, in silence, by a decaying taper, and amidst the solitude of a half-lighted apartment, it may redeem its character as a good ghost-story. Miss Seward always affirmed that she had derived her information from an authentic source, although she suppressed the names of the two persons chiefly concerned. I will not avail myself of any particulars I may have since received concerning the localities of the detail, but suffer them to rest under the same general description in which they were first related to me; and, for the same reason, I will not add to, or diminish the narrative, by any circumstance, whether more or less material, but simply rehearse, as I heard it, a story of supernatural terror.

About the end of the American war, when the officers of Lord Cornwallis’s army, which surrendered at Yorktown, and others, who had been made prisoners during t

he impolitic and ill-fated controversy, were returning to their own country, to relate their adventures, and repose themselves, after their fatigues; there was amongst them a general officer, to whom Miss S. gave the name of Browne, but merely, as I understood, to save the inconvenience of introducing a nameless agent in the narrative. He was an officer of merit, as well as a gentleman of high consideration for family and attainments.

Some business had carried General Browne upon a tour through the western counties, when, in the conclusion of a morning stage, he found himself in the vicinity of a small country town, which presented a scene of uncommon beauty, and of a character peculiarly English.

The little town, with its stately old church, whose tower bore testimony to the devotion of ages long past, lay amidst pastures and corn-fields of small extent, but bounded and divided with hedge-row timber of great age and size. There were few marks of modern improvement. The environs of the place intimated neither the solitude of decay, nor the bustle of novelty; the houses were old, but in good repair; and the beautiful little river murmured freely on its way to the left of the town, neither restrained by a dam, nor bordered by a towing-path.

Upon a gentle eminence, nearly a mile to the southward of the town, were seen, amongst many venerable oaks and tangled thickets, the turrets of a castle; as old as the wars of York and Lancaster, but which seemed to have received important alterations during the age of Elizabeth and her successor. It had not been a place of great size; but whatever accommodation it formerly afforded, was, it must be supposed, still to be obtained within its walls; at least, such was the inference which General Browne drew from observing the smoke arise merrily from several of the ancient wreathed and carved chimney-stalks. The wall of the park ran alongside of the highway for two or three hundred yards; and through the different points by which the eye found glimpses into the woodland scenery, it seemed to be well stocked. Other points of view opened in succession; now a full one, of the front of the old castle, and now a side glimpse at its particular towers; the former rich in all the bizarrerie of the Elizabethan school, while the simple and solid strength of other parts of the building seemed to show that they had been raised more for defence than ostentation.

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories

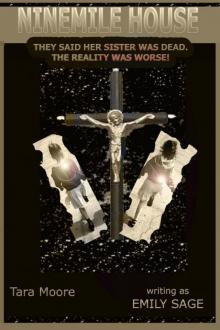

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Ninemile House

Ninemile House