- Home

- Tara Moore

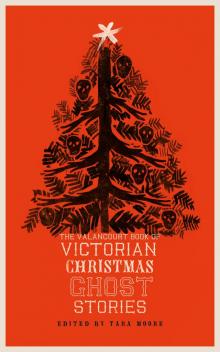

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Page 7

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Read online

Page 7

“A strange story I have just been told,” said he; “here has been my bailiff to inform me of the loss of four of the choicest ewes out of that little flock of Southdowns I set such store by, and which arrived in the north but two months since. And the poor creatures have been destroyed in so strange a manner, for their carcasses are horribly mangled.”

Most of us uttered some expression of pity or surprise, and some suggested that a vicious dog was probably the culprit.

“It would seem so,” said my father; “it certainly seems the work of a dog; and yet all the men agree that no dog of such habits exists near us, where, indeed, dogs are scarce, excepting the shepherds’ collies and the sporting dogs secured in yards. Yet the sheep are gnawed and bitten, for they show the marks of teeth. Something has done this, and has torn their bodies wolfishly; but apparently it has been only to suck the blood, for little or no flesh is gone.”

“How strange!” cried several voices. Then some of the gentlemen remembered to have heard of cases when dogs addicted to sheep-killing had destroyed whole flocks, as if in sheer wantonness, scarcely deigning to taste a morsel of each slain wether.

My father shook his head. “I have heard of such cases, too,” he said; “but in this instance I am tempted to think the malice of some unknown enemy has been at work. The teeth of a dog have been busy no doubt, but the poor sheep have been mutilated in a fantastic manner, as strange as horrible; their hearts, in especial, have been torn out, and left at some paces off, half-gnawed. Also, the men persist that they found the print of a naked human foot in the soft mud of the ditch, and near it—this.” And he held up what seemed a broken link of a rusted iron chain. Many were the ejaculations of wonder and alarm, and many and shrewd the conjectures, but none seemed exactly to suit the bearings of the case. And when my father went on to say that two lambs of the same valuable breed had perished in the same singular manner three days previously, and that they also were found mangled and gore-stained, the amazement reached a higher pitch.

Old Lady Speldhurst listened with calm intelligent attention, but joined in none of our exclamations. At length she said to my father, “Try and recollect—have you no enemy among your neighbours?”

My father started, and knit his brows. “Not one that I know of,” he replied; and indeed he was a popular man and a kind landlord.

“The more lucky you,” said the old dame, with one of her grim smiles.

It was now late, and we retired to rest before long. One by one the guests dropped off. I was the member of the family selected to escort old Lady Speldhurst to her room—the room I had vacated in her favour. I did not much like the office. I felt a remarkable repugnance to my godmother, but my worthy aunts insisted so much that I should ingratiate myself with one who had so much to leave, that I could not but comply. The visitor hobbled up the broad oaken stairs actively enough, propped on my arm and her ivory crutch. The room never had looked more genial and pretty, with its brisk fire, modern furniture, and the gay French paper on the walls.

“A nice room, my dear, and I ought to be much obliged to you for it, since my maid tells me it is yours,” said her ladyship; “but I am pretty sure you repent your generosity to me, after all those ghost stories, and tremble to think of a strange bed and chamber, eh?” I made some commonplace reply. The old lady arched her eyebrows. “Where have they put you, child?” she asked; “in some cockloft of the turrets, eh? or in a lumber-room—a regular ghost-trap? I can hear your heart beating with fear this moment. You are not fit to be alone.”

I tried to call up my pride, and laugh off the accusation against my courage, all the more, perhaps, because I felt its truth. “Do you want anything more that I can get you, Lady Speldhurst?” I asked, trying to feign a yawn of sleepiness.

The old dame’s keen eyes were upon me. “I rather like you, my dear,” she said, “and I liked your mamma well enough before she treated me so shamefully about the christening dinner. Now, I know you are frightened and fearful, and if an owl should but flap your window to-night, it might drive you into fits. There is a nice little sofa-bed in this dressing-closet—call your maid to arrange it for you, and you can sleep there snugly, under the old witch’s protection, and then no goblin dare harm you, and nobody will be a bit the wiser, or quiz you for being afraid.”

How little I knew what hung in the balance of my refusal or acceptance of that trivial proffer! Had the veil of the future been lifted for one instant! but that veil is impenetrable to our gaze. Yet, perhaps, she had a glimpse of the dim vista beyond, she who made the offer; for when I declined, with an affected laugh, she said, in a thoughtful, half abstracted manner, “Well, well! we must all take our own way through life. Good-night, child—pleasant dreams!” And I softly closed the door. As I did so, she looked round at me rapidly, with a glance I have never forgotten, half malicious, half sad, as if she had divined the yawning gulf that was to devour my young hopes. It may have been mere eccentricity, the odd phantasy of a crooked mind, the whimsical conduct of a cynical person, triumphant in the power of affrighting youth and beauty. Or, I have since thought, it may have been that this singular guest possessed some such gift as the Highland “second-sight,” a gift vague, sad, and useless to the possessor, but still sufficient to convey a dim sense of coming evil and boding doom. And yet, had she really known what was in store for me, what lurked behind the veil of the future, not even that arid heart could have remained impassive to the cry of humanity. She would, she must have snatched me back, even from the edge of the black pit of misery. But, doubtless, she had not the power. Doubtless she had but a shadowy presentiment, at any rate, of some harm to happen, and could not see, save darkly, into the viewless void where the wisest stumble.

I left her door. As I crossed the landing a bright gleam came from another room, whose door was left ajar; it (the light) fell like a bar of golden sheen across my path. As I approached, the door opened, and my sister Lucy, who had been watching for me, came out. She was already in a white cashmere wrapper, over which her loosened hair hung darkly and heavily, like tangles of silk.

“Rosa, love,” she whispered, “Minnie and I can’t bear the idea of your sleeping out there, all alone, in that solitary room—the very room, too, nurse Sherrard used to talk about! So, as you know Minnie has given up her room, and come to sleep in mine, still we should so wish you to stop with us to-night at any rate, and I could make up a bed on the sofa for myself, or you—and——”

I stopped Lucy’s mouth with a kiss. I declined her offer. I would not listen to it. In fact, my pride was up in arms, and I felt I would rather pass the night in the churchyard itself than accept a proposal dictated, I felt sure, by the notion that my nerves were shaken by the ghostly lore we had been raking up, that I was a weak, superstitious creature, unable to pass a night in a strange chamber. So I would not listen to Lucy, but kissed her, bade her good-night, and went on my way laughing, to show my light heart. Yet, as I looked back in the dark corridor, and saw the friendly door still ajar, the yellow bar of light still crossing from wall to wall, the sweet kind face still peering after me from amid its clustering curls, I felt a thrill of sympathy, a wish to return, a yearning after human love and companionship. False shame was strongest, and conquered. I waved a gay adieu. I turned the corner, and, peeping over my shoulder, I saw the door close; the bar of yellow light was there no longer in the darkness of the passage.

I thought, at that instant, that I heard a heavy sigh. I looked sharply round. No one was there. No door was open, yet I fancied, and fancied with a wonderful vividness, that I did hear an actual sigh breathed not far off, and plainly distinguishable from the groan of the sycamore branches, as the wind tossed them to and fro in the outer blackness. If ever a mortal’s good angel had cause to sigh for sorrow, not sin, mine had cause to mourn that night. But imagination plays us strange tricks, and my nervous system was not over-composed, or very fitted for judicial analysis. I had to go through the picture-gallery. I had never entered this apartme

nt by candle-light before, and I was struck by the gloomy array of the tall portraits, gazing moodily from the canvas on the lozenge-paned or painted windows, which rattled to the blast as it swept howling by. Many of the faces looked stern, and very different from their daylight expression. In others, a furtive flickering smile seemed to mock me, as my candle illumined them; and in all, the eyes, as usual with artistic portraits, seemed to follow my motions with a scrutiny and an interest the more marked for the apathetic immovability of the other features. I felt ill at ease under this stony gaze, though conscious how absurd were my apprehensions; and I called up a smile and an air of mirth, more as if acting a part under the eyes of human beings, than of their mere shadows on the wall. I even laughed as I confronted them. No echo had my short-lived laughter but from the hollow armour and arching roof, and I continued on my way in silence. I have spoken of the armour. Indeed, there was a fine collection of plate and mail, for my father was an enthusiastic antiquary. In especial there were two suits of black armour, erect, and surmounted by helmets with closed visors, which stood as if two mailed champions were guarding the gallery and its treasures. I had often seen these, of course, but never by night, and never when my whole organisation was so overwrought and tremulous as it then was. As I approached the Black Knights, as we had dubbed them, a wild notion seized on me that the figures moved, that men were concealed in the hollow shells which had once been borne in battle and tourney. I knew the idea was childish, yet I approached in irrational alarm, and fancied I absolutely beheld eyes glaring on me from the eyelet-holes in the visors. I passed them by, and then my excited fancy told me that the figures were following me with stealthy strides. I heard a clatter of steel, caused, I am sure, by some more violent gust of wind sweeping the gallery through the crevices of the old windows, and with a smothered shriek I rushed to the door, opened it, darted out, and clapped it to with a bang that reechoed through the whole wing of the house. Then by a sudden and not uncommon revulsion of feeling, I shook off my aimless terrors, blushed at my weakness, and sought my chamber only too glad that I had been the only witness of my late tremors.

As I entered my chamber, I thought I heard something stir in the neglected lumber-room, which was the only neighbouring apartment. But I was determined to have no more panics, and resolutely shut my ears to this slight and transient noise, which had nothing unnatural in it; for surely, between rats and wind, an old manor-house on a stormy night needs no sprites to disturb it. So I entered my room, and rang for my maid. As I did so, I looked around me, and a most unaccountable repugnance to my temporary abode came over me, in spite of my efforts. It was no more to be shaken off than a chill is to be shaken off when we enter some damp cave. And, rely upon it, the feeling of dislike and apprehension with which we regard, at first sight, certain places and people, was not implanted in us without some wholesome purpose. I grant it is irrational—mere animal instinct—but is not instinct God’s gift, and is it for us to despise it? It is by instinct that children know their friends from their enemies—that they distinguish with such unerring accuracy between those who like them and those who only flatter and hate them. Dogs do the same; they will fawn on one person, they slink snarling from another. Show me a man whom children and dogs shrink from, and I will show you a false, bad man—lies on his lips, and murder at his heart. No; let none despise the heaven-sent gift of innate antipathy, which makes the horse quail when the lion crouches in the thicket—which makes the cattle scent the shambles from afar, and low in terror and disgust as their nostrils snuff the blood-polluted air. I felt this antipathy strongly as I looked around me in my new sleeping-room, and yet I could find no reasonable pretext for my dislike. A very good room it was, after all, now that the green damask curtains were drawn, the fire burning bright and clear, candles burning on the mantelpiece, and the various familiar articles of toilet arranged as usual. The bed, too, looked peaceful and inviting—a pretty little white bed, not at all the gaunt funereal sort of couch which haunted apartments generally contain.

My maid entered, and assisted me to lay aside the dress and ornaments I had worn, and arranged my hair, as usual, prattling the while, in Abigail fashion. I seldom cared to converse with servants; but on that night a sort of dread of being left alone—a longing to keep some human being near me—possessed me, and I encouraged the girl to gossip, so that her duties took her half an hour longer to get through than usual. At last, however, she had done all that could be done, and all my questions were answered, and my orders for the morrow reiterated and vowed obedience to, and the clock on the turret struck one. Then Mary, yawning a little, asked if I wanted anything more, and I was obliged to answer No, for very shame’s sake; and she went. The shutting of the door, gently as it was closed, affected me unpleasantly. I took a dislike to the curtains, the tapestry, the dingy pictures—everything. I hated the room. I felt a temptation to put on a cloak, run, half-dressed, to my sisters’ chamber, and say I had changed my mind, and come for shelter. But they must be asleep, I thought, and I could not be so unkind as to wake them. I said my prayers with unusual earnestness and a heavy heart. I extinguished the candles, and was just about to lay my head on my pillow, when the idea seized me that I would fasten the door. The candles were extinguished, but the fire-light was amply sufficient to guide me.

I gained the door. There was a lock, but it was rusty or hampered; my utmost strength could not turn the key. The bolt was broken and worthless. Baulked of my intention, I consoled myself by remembering that I had never had need of fastenings yet, and returned to my bed. I lay awake for a good while, watching the red glow of the burning coals in the grate. I was quiet now, and more composed. Even the light gossip of the maid, full of petty human cares and joys, had done me good—diverted my thoughts from brooding. I was on the point of dropping asleep, when I was twice disturbed. Once, by an owl, hooting in the ivy outside—no unaccustomed sound, but harsh and melancholy; once, by a long and mournful howling set up by the mastiff, chained in the yard beyond the wing I occupied. A long-drawn, lugubrious howling, was this latter; and much such a note as the vulgar declare to herald a death in the family. This was a fancy I had never shared; but yet I could not help feeling that the dog’s mournful moans were sad, and expressive of terror, not at all like his fierce, honest bark of anger, but rather as if something evil and unwonted were abroad. But soon I fell asleep.

How long I slept, I never knew. I awoke at once, with that abrupt start which we all know well, and which carries us in a second from utter unconsciousness to the full use of our faculties. The fire was still burning, but was very low, and half the room or more was in deep shadow. I knew, I felt, that some person or thing was in the room, although nothing unusual was to be seen by the feeble light. Yet it was a sense of danger that had aroused me from slumber. I experienced, while yet asleep, the chill and shock of sudden alarm, and I knew, even in the act of throwing off sleep like a mantle, why I awoke, and that some intruder was present. Yet, though I listened intently, no sound was audible, except the faint murmur of the fire,—the dropping of a cinder from the bars—the loud irregular beatings of my own heart.

Notwithstanding this silence, by some intuition I knew that I had not been deceived by a dream, and felt certain that I was not alone. I waited. My heart beat on; quicker, more sudden grew its pulsations, as a bird in a cage might flutter in presence of the hawk. And then I heard a sound, faint, but quite distinct, the clank of iron, the rattling of a chain! I ventured to lift my head from the pillow. Dim and uncertain as the light was, I saw the curtains of my bed shake, and caught a glimpse of something beyond, a darker spot in the darkness. This confirmation of my fears did not surprise me so much as it shocked me. I strove to cry aloud, but could not utter a word. The chain rattled again, and this time the noise was louder and clearer. But though I strained my eyes, they could not penetrate the obscurity that shrouded the other end of the chamber, whence came the sullen clanking. In a moment several distinct trains of thought, like many-colou

red strands of thread twining into one, became palpable to my mental vision. Was it a robber? could it be a supernatural visitant? or was I the victim of a cruel trick, such as I had heard of, and which some thoughtless persons love to practise on the timid, reckless of its dangerous results? And then a new idea, with some ray of comfort in it, suggested itself. There was a fine young dog of the Newfoundland breed, a favourite of my father’s, which was usually chained by night in an outhouse. Neptune might have broken loose, found his way to my room, and, finding the door imperfectly closed, have pushed it open and entered. I breathed more freely as this harmless interpretation of the noise forced itself upon me. It was—it must be—the dog, and I was distressing myself uselessly. I resolved to call to him; I strove to utter his name—“Neptune, Neptune!” but a secret apprehension restrained me, and I was mute. Then the chain clanked nearer and nearer to the bed, and presently I saw a dusky shapeless mass appear between the curtains on the opposite side to where I was lying. How I longed to hear the whine of the poor animal that I hoped might be the cause of my alarm. But no; I heard no sound save the rustle of the curtains and the clash of the iron chain. Just then the dying flame of the fire leaped up, and with one sweeping hurried glance I saw that the door was shut, and, horror! it is not the dog! it is the semblance of a human form that now throws itself heavily on the bed, outside the clothes, and lies there, huge and swart, in the red gleam that treacherously dies away after showing so much to affright, and sinks into dull darkness.

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories

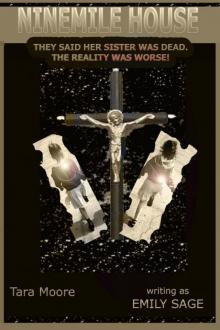

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Ninemile House

Ninemile House