- Home

- Tara Moore

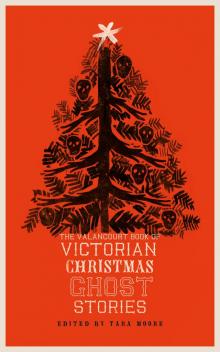

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Page 15

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Read online

Page 15

I was intensely horrified, but still I retained sufficient self-consciousness to be struck professionally by such a phenomenon.

Surely there was something more than supernatural agency in all this?

Again I scrutinised the dead face, and even the throat and chest; but, with the exception of a tiny pimple on one temple beneath a cluster of hair, not a mark appeared. To look at the corpse, one would have believed that this man had indeed died by the visitation of God, peacefully, whilst sleeping.

How long I stood there I know not, but time enough to gather my scattered senses and to reflect that, all things considered, my own position would be very unpleasant if I was found thus unexpectedly in the room of the mysteriously dead man.

So, as noiselessly as I could, I made my way out of the house. No one met me on the private staircase; the little door opening into the road was easily unfastened; and thankful indeed was I to feel again the fresh wintry air as I hurried along that road by the churchyard.

There was a magnificent funeral soon in that church; and it was said that the young widow of the buried man was inconsolable; and then rumours got abroad of a horrible apparition which had been seen on the night of the death; and it was whispered the young widow was terrified, and insisted upon leaving her splendid mansion.

I was too mystified with the whole affair to risk my reputation by saying what I knew, and I should have allowed my share in it to remain for ever buried in oblivion, had I not suddenly heard that the widow, objecting to many of the legacies in the last will of her husband, intended to dispute it on the score of insanity, and then there gradually arose the rumour of his belief in having received a mysterious summons.

On this I went to the lawyer, and sent a message to the lady, that, as the last person who had attended her husband, I undertook to prove his sanity; and I besought her to grant me an interview, in which I would relate as strange and horrible a story as ear had ever heard.

The same evening I received an invitation to go to the mansion.

I was ushered immediately into a splendid room, and there, standing before the fire, was the most dazzlingly beautiful young creature I had ever seen.

She was very small, but exquisitely made; had it not been for the dignity of her carriage, I should have believed her a mere child.

With a stately bow she advanced, but did not speak.

“I come on a strange and painful errand,” I began, and then I started, for I happened to glance full into her eyes, and from them down to the small right hand grasping the chair. The wedding-ring was on that hand!

“I conclude you are the Mr. Read who requested permission to tell me some absurd ghost-story, and whom my late husband mentions here.” And as she spoke she stretched out her left hand towards something—but what I knew not, for my eyes were fixed on that hand.

Horror! White and delicate it might be, but it was shaped like a claw, and the third finger was missing!

One sentence was enough after that. “Madam, all I can tell you is, that the ghost who summoned your husband was marked by a singular deformity. The third finger of the left hand was missing,” I said sternly; and the next instant I had left that beautiful sinful presence.

That will was never disputed. The next morning, too, I received a check for a thousand pounds; and the next news I heard of the widow was, that she had herself seen that awful apparition, and had left the mansion immediately.

JACK LAYFORD’S FRIEND

WITH AN ACCOUNT OF HOW HE LAID THE GHOST

A Christmas Story

When Mary Elizabeth Braddon named her monthly magazine Belgravia, she had every intention of harnessing the elegance associated with that London neighborhood. This story by an anonymous author certainly emphasizes class boundaries as it demonizes the governess in a number of ways. The description of her appearance includes a racial slur; the offensive term appears four times in that 1869 volume of Belgravia, attesting to its perceived acceptance among middle-class Victorian readers.

CHAPTER I

“I’m afraid you’ll have but a dull time of it, old fellow; it isn’t too late to write, and say we find we can’t manage it, even now; not but that the poor old guv would be awfully cut up, and the girls too, for that matter.”

“I wouldn’t disappoint them for the world,” broke in the individual addressed; “so that’s settled. As for being slow, or anything of that sort, it’s never slow with plenty of girls in the house.”

“O, there’s plenty of ’em, if that’s all,” rejoined the first speaker; and his tone, to one who did not know him as his friend did, might perhaps have sounded just a trifle unappreciative of the blessing; “but when it’s a fellow’s sisters, you know—”

“Yes, but then you see, my dear Jack, in my case it’s another fellow’s sisters. So, come, pack up your traps; and then hurrah for the governor and the girls!”

Jack, thus adjured, said no more. The hint that even now, at the eleventh hour, there was yet time to reconsider their plans, had been thrown out, truth to tell, and his friend knew, in no anxiety of Jack’s for himself. Indeed it is to be more than doubted if the disappointment of either the “governor” or the girls would have greatly exceeded Jack’s own, had his suggestion of giving up the projected home-visit been differently received. So that was settled. An hour or so later, and the December fog was stealing down on the dingy London streets and over its murky river; but Jack Layford and his friend were leaving it all—river, streets, and fog—fast behind them, as, tearing, puffing, snorting, they sped on their iron road eastward.

“Only a couple of years,” Jack is saying from his snug corner of the first-class G. E. railway carriage that they have contrived to secure all to themselves,—“only a couple of years! I can scarcely believe it; and to think that we might never have known each other at all, Phil, if it hadn’t been for that jolly old umbrella of mine!”

And Jack spoke truth; but for the said umbrella the two friends might never have been even acquaintances. East and west, just so far apart, had their courses lain. East, Jack Layford; west, Philip Carlyon. So far west indeed the latter, that he could not well have made it farther; unless, that is, he had quitted terra firma altogether and taken to the sea. East and west through school-days and college-days. Then had come the world (which was London) and Jack Layford’s umbrella (on Phil Carlyon’s toes); and east and west had met at last, to be east and west no longer.

Jack loved to go over the story of that first meeting; how, seated side by side in the pit of the Haymarket one raw November evening, strangers both in the great city, they had stolen shy glances at one another, it might be, but nothing more; until the row at the end, “when I brought that umbrella of mine down on your ‘patents,’ Phil, and you swore; and then there was supper together at Evans’s; and that’s how it all came about, eh, old fellow?”

But, as Jack says, two years ago all this. Friends now; Damon and Pythias, with various other small and harmless jokes at the two’s expense; but Damon and Pythias knowing very little of one another’s personal history and belongings, as is not unfrequently the case when the surnames of those gentlemen happen to be Bull. Layford, for instance, knew in a kind of general way that his friend Carlyon was an only child, with an adoring mother down at some outlandish-sounding place in Cornwall, to which he vanished now and then for a week or so, as the fit took him; knew also that he had an income of some sort, and concluded it to be a good one; rides in the Row, balls, fêtes, &c. in the season, with the moors or Norway for the vacation months, being a state of things scarcely attainable by the present means of so many dinners a week during term-time, with a remote contingency of briefs in the future. Again, with Carlyon, he, for his part, had a kind of vague knowledge of his friend Jack being one of a large family, the rest of which were girls; knew, furthermore, that there was no mother, and that “the guv,” as Jack was irreverently given to term him, was the best of old fellows, and farmed some hundreds of acres down in Suffolk, as other Layfords had done

before him time out of mind; and lastly, though not least, that he made the said Jack a very fair allowance, though he had been ever so little disappointed when that young gentleman had suddenly announced his intention of renouncing the church for something more substantial in the shape of common law.

“Here we are, old fellow, home at last!”

And how home-like the old house gleamed through the winter’s night! a little foggy, even down here. Home-like even to Philip Carlyon’s eyes, to whom it brought no memories, no associations; home-like indeed to honest Jack’s, to whom it brought both things.

Jack scarcely waited for the dog-cart to stop; down went the reins, and Philip saw his big friend standing in a flood of light, the centre of a grand complication of female arms and heads, in the old-fashioned hall, before he himself had time to make his more leisurely descent. The young Cornishman stood for a moment irresolute, and with a feeling of something very like shyness, in the open doorway. But it was only for a moment. The old Squire had spied him out.

“Come in, sir; come in!” cried Jack’s governor, dragging his visitor by the hand, and shaking it warmly at the same time. “Why, Jack, sir, what are you thinking about, eh?”

“I can’t help it, sir,” cried poor Jack deprecatingly, and making an effort at freedom; “it’s the girls.”

But the girls had caught sight of the stranger by this time, and falling back, a laughing, blushing group, gave Jack his liberty.

“I see I needn’t introduce you to the governor, Carlyon,” said Jack with a nod, as he endeavoured to restore to something like order his ruffled plumes; “and these are the girls.” Having said which, Jack appeared to consider that he had fulfilled the whole duty of man under the circumstances, and proceeded forthwith to suggest hot water in the bedrooms, and something to eat in the dining-room as soon as practicable.

If Philip Carlyon had found the old house home-like in that view of it from the outside, he found the great dining-room with its panelled walls, blazing fire, and soft lamp-light, with tea awaiting them, more home-like still. Perhaps it was not just these things alone that served to give the home-like look. There was a something there that Philip Carlyon’s home, happy as it might have been, had never known. There was the old Squire, firm and stalwart still, with his cheery voice and bright keen eyes, and hair too that was crisp as ever, if the dark brown was here and there streaked with gray. And there were the girls. Philip began counting them to himself, and wondering which was which, for Jack had in a measure accustomed him to their names. There was one Phil knew must be Miss Layford. She it was who made the tea, attended to the Squire, and was moreover evidently an authority with the rest. Jack sat next her; and Phil thought that if the choice had been given him, he might perhaps have chosen that seat too. She was not much like Jack, this eldest sister, excepting that she was rather tall, taller by some inches than any of the other girls—though more than half of them, it is true, had not yet done growing, even among the bigger ones. Then if she was not exactly what could be called dark—nothing like so dark as Philip himself, for instance—she had certainly nothing of Jack’s fairness.

Philip came to the decision, by the time that tea was over, that Miss Layford’s hair must be chestnut, and her eyes—well, chestnut too. Great soft brown eyes, with a dash of red gold in them—he had a favourite dog at home with just such eyes. But Miss Layford’s guest—desirable in his eyes as that occupation might have seemed—could not sit staring at her all tea-time.

There was a lady seated opposite him, at whom—had his taste in the matter been consulted—Philip Carlyon would perhaps rather not have looked at all; and yet he did look more than once, and was savage with himself in consequence. Not one of the family, as he easily discovered, for she was addressed as Miss Dormer. She appeared to have the charge of the half-dozen or so of girls seated near; among them two little ones, twins evidently—with round curly heads, fair, like Jack’s, and very round eyes, blue, also like Jack’s—who stared shyly at the strange guest, reminding him forcibly of two little robins on the look-out for crumbs. “She’s the governess,” said Phil to himself; “but then why is she here in the holidays?”

After a time he found himself asking why she was there at all, and finally came to the decision that he would not sit opposite her again if he could help it. Her eyes offended him. “Confound her, why can’t she keep ’em to herself!” he growled; “they’re like gimlets, by Jove!” Even the unfortunate young woman’s hair must needs irritate him; and yet it was such hair as all the “Macassar” of Rowland6 and his tribe could scarcely have induced on half-a-dozen heads in the United Kingdom,—luxuriant, black—raven black. “She’s a nigger, I believe,” was Phil’s final conclusion; “only she’s managed to get some of the dye out of her hands and face.” But the round of observation was not yet complete—“the girls” were by no means exhausted. There was one, for instance, seated next Philip, Flop by name—self-achieved, as he shortly discovered—with whom—after she had all but deposited a cup of tea in his lap, and had dropped her spoon, knife, and various other trifles below the table, which he had been under the necessity of diving for and recovering—he found himself on terms of almost brotherly intimacy. Then there was Emmy, and Lotty, and Bessie; though which was which, together with a few other little details connected with them, was a subject upon which our friend Philip’s ideas were at present a trifle misty.

6 A hair oil much advertised in the Victorian period.

In the drawing-room, after tea, Phil found these little matters gradually resolving themselves, as was natural. And now, if Jack Layford’s friend had been disposed to envy him his position at the tea-table, how much more so when, Miss Layford having seated herself at the piano, that lucky young giant was at her side once more, turning over the leaves and calling her Margaret, while she, smiling and obedient, gave him song after song as it was called for! And all this while Phil was being literally held by the button by the somewhat prosy old Squire. After a time Miss Dormer went to the piano, but Jack did not turn over the leaves for her; and Philip, free by this time—feeling horribly rude all the while—would not make the offer; so it fell to the lot of the good-natured Flop—after, it is to be premised, she had by way of inauguration brought down the walnut-wood “what-not” and its load with a horrible crash to the ground. Nor had Philip Miss Layford even for an excuse, she having been called from the room just at the moment at which she rose from the piano; and although Phil kept a sharp look-out on the door, she did not return until the innocent Squire had once more captured his unwary guest. On the whole, perhaps the evening might, so far as our friend was concerned, have been more successful; but Phil consoled himself with the determination before he went to sleep that night to manage affairs better in future.

In accordance with which resolution, when Jack Layford descended to the breakfast-table the next morning, resplendent in pink and cords, he found another figure—not quite such a massive or brilliant one it may be, but quite as faultlessly turned out—in the field before him. There, seated at Margaret’s side, assisting her with the coffee-pot, buttering her toast, laughing, talking the while, doing everything in short just as if he had been the veritable Jack himself, sat Mr. Philip Carlyon. Was it Philip’s fancy, or did Jack’s bright face really cloud over at the sight? But for the utter absurdity of the thing, Philip could almost have said that it was so. Jack was certainly restless that morning. He wandered from the table to the sideboard, fluttered from cold meat to hot, and ended by eating neither. His principal occupation seemed to be watching the two at the head of the table; while Miss Dormer’s attention appeared to be divided among the three.

“Come, Carlyon,” cried Jack at last, “I think before the day is over you will wish you had eaten your breakfast instead of talking.”

But Carlyon only laughed.

“Mr. Carlyon does not agree with you.” The voice was Miss Dormer’s.

Mr. Carlyon was looking red now, Jack black, and Miss Layford—well, rathe

r red also. At this moment the Squire came innocently to the general rescue.

“Well, if you won’t really take any more, Mr. Carlyon, I think we may as well be getting off.”

“I am ready, sir,” said Phil, rising.

Jack had already disappeared; and in a few minutes the girls had the old house to themselves.

There was a late dinner that day; and the evening was passed much the same as the previous one had been, with this exception, that Philip, strong in his resolution of the past night, did somehow contrive to manage affairs more to his own satisfaction. In the first place, he secured the much-desired post at Miss Layford’s piano, turned over the leaves and chose the songs, just as that lucky Jack had done the night before. He even condescended so far as to smile on his pet aversion, the governess, when her turn came; and, sitting by Margaret’s side in some far-off corner, made no sign of impatience throughout the entire performance. And Jack? From the chess-table, over which he sat with the “guv,” he cast so many restless glances at the far-off corner, made so many extraordinary moves, and was finally so evidently lost as to his own position in the game, or his adversary’s either, that the Squire at last good-naturedly sent him off to join his friend. But of this permission Jack did not avail himself. He made his way to the piano instead, dethroned Flop, again on duty, not in the gentlest manner, and was Miss Dormer’s humble slave for the rest of the evening.

The little black-eyed governess flushed a little as Jack came up.

“You find it dull,” she said softly; “and you want poor little nobody to take pity on you; so even I am of use sometimes, Mr. Layford?”

She was not looking at him; the dark eyes, with a strange light in them, were on the stray couple, whispering and smiling together in the distant corner. Jack’s eyes followed hers, as it was just possible she had intended they should do. It was only for a moment; then he turned them once more on her, and Miss Dormer knew that there was an angry flash in them, but not for her.

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories

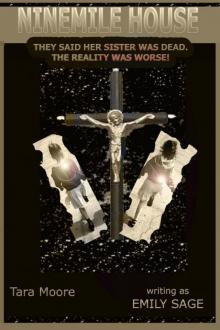

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Ninemile House

Ninemile House