- Home

- Tara Moore

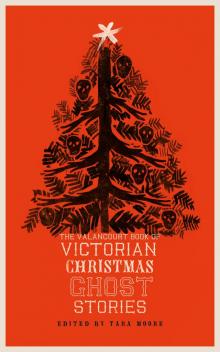

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Page 14

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Read online

Page 14

It would be too much to say that she had no uncomfortable sensation, or that she did not peer into the darkness ahead, and occasionally take an anxious glance over her shoulder, or that she altogether felt sure that she should not see old Hooker gliding before her, or noiselessly coming up behind her. She could not help allowing all the ghost stories she had ever heard to pass in ghastly review through her mind. Still she tried not to walk faster than she should otherwise have done; indeed, she foresaw that if she attempted to run, the wax taper she held would most probably be blown out. This, strong-minded as she was, she would very much rather should not happen. The keen wind of Christmas was blowing outside, and blasts here and there found their way along the passages, in consequence of one or two doors which ought to have been shut having been left open.

Huntingfield Hall was an old edifice, and the same attention to warming the passages and shutting out the wind had not been paid when it was constructed as is the case in more modern buildings. The young lady saw before her a door partly open, but which seemed at that moment about to close with a slam. To prevent this, forgetting her former caution, she darted forward, when the same blast which, as she supposed, was moving the door, blew out her candle. She knew her way, and remembered that a few paces farther on there were two steps, down which she might fall if not careful. A creeping feeling of horror, however, stole over her when, as she attempted to advance, she felt herself held back. It must be fancy. She made another effort, and again was unable to move forward. Her heart did, indeed, now beat quickly. She would have screamed for help, but she was not given to screaming, and her voice failed her. Once more she tried to run on, but she felt herself in the grasp of some supernatural power, as a person feels in a dream when unable to proceed. Her courage at length gave way, every moment she expected to hear a peal of mocking laughter from the fiend who held her, for her imagination was now worked up to a pitch which would have made anything, however dreadful, appear possible. At length, by an effort, she cried out:

“Help me! help! Pray come here!”

The words had scarcely left her lips when a door in the passage opened, and she saw a person hurrying with a light towards her.

“Thanks, thanks, Henry!” she exclaimed, giving way to an hysterical laugh, as she sank into the arms of Captain Fotheringsail, feeling now perfectly secure against all enemies, either of a supernatural or natural character.

“What is the matter, dearest?” he asked, in a voice of alarm.

“Oh, nothing, nothing. My candle went out, and I felt myself unable to move on,” she answered.

“I see you could not, for the skirt of your dress and your shawl have both caught in the door,” he exclaimed, with a merry laugh, which did more than a dose of sal volatile or camphor would have done to dispel her fears, and, taking his arm, she accompanied him to the ball-room.

Should she tell him of the reappearance of old Hooker, or some living representative? Why not? She hoped always to have the privilege of enjoying his perfect confidence, and giving hers in return, so she told him what she had seen, or fancied that she had seen, assuring him at the same time that she did not believe her visitor had intended to come to her room. Again he gave way to a peal of merry laughter, and exclaimed:

“I am delighted to hear it, for now he will be caught to a certainty. I have not the slightest doubt that he intends again to visit either the ball-room or the servants’-hall, but whenever he comes we will be ready for him. I have an idea that your wild young cousin and his friend have no little to do with the trick, for I have ascertained that they arrived at the Hall some hours before they made their appearance in the ball-room in the character of sailors. When I saw their proceedings I rather regretted the character I had assumed, lest I should have been taken for one of the party.”

The guests were assembling in the ball-room as the captain and Jane reached it. People looked at them and smiled significantly, and some of them said, “I thought it would be so.” One or two remarked, “Well, it is curious how the dark girls cut out the fair ones. Who would have thought that that little Miss Otterburn would have been preferred to her cousins the Ildertons? Lady Ilderton won’t thank her, I think.” However, Lady Ilderton was as much pleased when she heard that Captain Fotheringsail, whom she liked very much, had proposed to her niece, as if he had made an offer to one of her daughters; and so people, for once in a way, were wrong.

Captain Fotheringsail and Jane at once separated from each other, and went round to each of the guests separately, whispering in their ears. They instantly formed themselves into a quadrille, and the musicians struck up. On this the captain slipped from the side of his partner, and adroitly ran a dark thin line across the room, almost the height of a man’s knee from the floor.

The quadrille was concluded and nothing happened. A valse was gone through, and then another quadrille was played. It seemed, however, that if the captain had hopes of catching the ghost, the ghost was not to be caught. He begged Cousin Giles to ascertain whether old Hooker had appeared in the servants’-hall, or anywhere about the house. Cousin Giles had assured him that he knew nothing at all about the matter, and was on the point of going to perform his commission, when, from the exact spot where the ghost had appeared on the previous day, forth he stalked, looking quite as dreadful as before. The guests ran from side to side to let him pass, when just as he reached the middle of the room he stumbled, made an attempt to jump, and then down he came full length on the floor. Off came a head and a pair of shoulders, and then was seen the astonished and somewhat frightened countenance of the simple Simon Langdon, who exclaimed, “Oh, Charley, Charley, I didn’t think you were going to play me that trick.” Finding that the trick was discovered, Charley dashed out from behind a screen with a tin tube and lamp in his hand, and blew a superb blue flame over Simon, who was quickly divested of his hunting-dress amid the laughter of the guests. Charley and his friend confessed that they had induced Simon to act the ghost that evening, though who had played it the previous one they did not say.

“Well, young gentlemen, you have had your fun, and no harm has been done, though the consequences might have been more serious than you anticipated,” said Sir Gilbert. “It requires no large amount of wit to impose on the credulous, as the spirit-rappers and mediums have shown us, and as we may learn by the exhibition of my young friend here and his coadjutors.” And the baronet looked very hard at Simon and Charley. He then added, in his usual good-natured tone, “However, as I said, no mischief has been done, though I must have it clearly understood that I cannot again allow old Hooker’s ghost to make his appearance at Huntingfield Hall.”

Note.—The author has to state, that there is more truth in this story than may generally be supposed. A ghost, or spirit of some sort, was believed by a whole neighbourhood to have paid occasional visits to members of his own family, and it was not till after the lapse of many years that one of them by chance heard of the story, which had not even the shadow of a foundation.

Ada Buisson

THE GHOST’S SUMMONS

It was common for the ghostly tales in periodicals to be narrated by domestic servants. In Gaskell’s “The Old Nurse’s Story,” for example, the nurse has intimate access to the family but remains outside of their confidence. In this dramatic tale, a rich man employs a doctor to serve in a similar role; the doctor witnesses a confusing, uncanny scene, but he remains ignorant of the full story. The scant details of the scene merely suggest the story behind an unusual deathbed, one that seems to have been brought about by an act both premeditated and unavenged. This story originally appeared in Belgravia in January 1868.

“Wanted, sir—a patient.”

It was in the early days of my professional career, when patients were scarce and fees scarcer; and though I was in the act of sitting down to my chop, and had promised myself a glass of steaming punch afterwards, in honour of the Christmas season, I hurried instantly into my surgery.

I entered briskly; but no sooner di

d I catch sight of the figure standing leaning against the counter than I started back with a strange feeling of horror which for the life of me I could not comprehend.

Never shall I forget the ghastliness of that face—the white horror stamped upon every feature—the agony which seemed to sink the very eyes beneath the contracted brows; it was awful to me to behold, accustomed as I was to scenes of terror.

“You seek advice,” I began, with some hesitation.

“No; I am not ill.”

“You require then—”

“Hush!” he interrupted, approaching more nearly, and dropping his already low murmur to a mere whisper. “I believe you are not rich. Would you be willing to earn a thousand pounds?”

A thousand pounds! His words seemed to burn my very ears.

“I should be thankful, if I could do so honestly,” I replied with dignity. “What is the service required of me?”

A peculiar look of intense horror passed over the white face before me; but the blue-black lips answered firmly, “To attend a death-bed.”

“A thousand pounds to attend a death-bed! Where am I to go, then?—whose is it?”

“Mine.”

The voice in which this was said sounded so hollow and distant, that involuntarily I shrank back. “Yours! What nonsense! You are not a dying man. You are pale, but you appear perfectly healthy. You—”

“Hush!” he interrupted; “I know all this. You cannot be more convinced of my physical health than I am myself; yet I know that before the clock tolls the first hour after midnight I shall be a dead man.”

“But—”

He shuddered slightly; but stretching out his hand commandingly, motioned me to be silent. “I am but too well informed of what I affirm,” he said quietly; “I have received a mysterious summons from the dead. No mortal aid can avail me. I am as doomed as the wretch on whom the judge has passed sentence. I do not come either to seek your advice or to argue the matter with you, but simply to buy your services. I offer you a thousand pounds to pass the night in my chamber, and witness the scene which takes place. The sum may appear to you extravagant. But I have no further need to count the cost of any gratification; and the spectacle you will have to witness is no common sight of horror.”

The words, strange as they were, were spoken calmly enough; but as the last sentence dropped slowly from the livid lips, an expression of such wild horror again passed over the stranger’s face, that, in spite of the immense fee, I hesitated to answer.

“You fear to trust to the promise of a dead man! See here, and be convinced,” he exclaimed eagerly; and the next instant, on the counter between us lay a parchment document; and following the indication of that white muscular hand, I read the words, “And to Mr. Frederick Read, of 14 High-street, Alton, I bequeath the sum of one thousand pounds for certain service rendered to me.”

“I have had that will drawn up within the last twenty-four hours, and I signed it an hour ago, in the presence of competent witnesses. I am prepared, you see. Now, do you accept my offer, or not?”

My answer was to walk across the room and take down my hat, and then lock the door of the surgery communicating with the house.

It was a dark, icy-cold night, and somehow the courage and determination which the sight of my own name in connection with a thousand pounds had given me, flagged considerably as I found myself hurried along through the silent darkness by a man whose death-bed I was about to attend.

He was grimly silent; but as his hand touched mine, in spite of the frost, it felt like a burning coal.

On we went—tramp, tramp, through the snow—on, on, till even I grew weary, and at length on my appalled ear struck the chimes of a church-clock; whilst close at hand I distinguished the snowy hillocks of a churchyard.

Heavens! was this awful scene of which I was to be the witness to take place veritably amongst the dead?

“Eleven,” groaned the doomed man. “Gracious God! but two hours more, and that ghostly messenger will bring the summons. Come, come; for mercy’s sake, let us hasten.”

There was but a short road separating us now from a wall which surrounded a large mansion, and along this we hastened until we reached a small door.

Passing through this, in a few minutes we were stealthily ascending the private staircase to a splendidly-furnished apartment, which left no doubt of the wealth of its owner.

All was intensely silent, however, through the house; and about this room in particular there was a stillness that, as I gazed around, struck me as almost ghastly.

My companion glanced at the clock on the mantelshelf, and sank into a large chair by the side of the fire with a shudder. “Only an hour and a half longer,” he muttered. “Great heaven! I thought I had more fortitude. This horror unmans me.” Then, in a fiercer tone, and clutching my arm, he added, “Ha! you mock me, you think me mad; but wait till you see—wait till you see!”

I put my hand on his wrist; for there was now a fever in his sunken eyes which checked the superstitious chill which had been gathering over me, and made me hope that, after all, my first suspicion was correct, and that my patient was but the victim of some fearful hallucination.

“Mock you!” I answered soothingly. “Far from it; I sympathise intensely with you, and would do much to aid you. You require sleep. Lie down, and leave me to watch.”

He groaned, but rose, and began throwing off his clothes; and watching my opportunity, I slipped a sleeping-powder, which I had managed to put in my pocket before leaving the surgery, into the tumbler of claret that stood beside him.

The more I saw, the more I felt convinced that it was the nervous system of my patient which required my attention; and it was with sincere satisfaction I saw him drink the wine, and then stretch himself on the luxurious bed.

“Ha,” thought I, as the clock struck twelve, and instead of a groan, the deep breathing of the sleeper sounded through the room; “you won’t receive any summons to-night, and I may make myself comfortable.”

Noiselessly, therefore, I replenished the fire, poured myself out a large glass of wine, and drawing the curtain so that the firelight should not disturb the sleeper, I put myself in a position to follow his example.

How long I slept I know not, but suddenly I aroused with a start and as ghostly a thrill of horror as ever I remember to have felt in my life.

Something—what, I knew not—seemed near, something nameless, but unutterably awful.

I gazed round.

The fire emitted a faint blue glow, just sufficient to enable me to see that the room was exactly the same as when I fell asleep, but that the long hand of the clock wanted but five minutes of the mysterious hour which was to be the death-moment of the “summoned” man!

Was there anything in it, then?—any truth in the strange story he had told?

The silence was intense.

I could not even hear a breath from the bed; and I was about to rise and approach, when again that awful horror seized me, and at the same moment my eye fell upon the mirror opposite the door, and I saw—

Great heaven! that awful Shape—that ghastly mockery of what had been humanity—was it really a messenger from the buried, quiet dead?

It stood there in visible death-clothes; but the awful face was ghastly with corruption, and the sunken eyes gleamed forth a green glassy glare which seemed a veritable blast from the infernal fires below.

To move or utter a sound in that hideous presence was impossible; and like a statue I sat and saw that horrid Shape move slowly towards the bed.

What was the awful scene enacted there, I know not. I heard nothing, except a low stifled agonised groan; and I saw the shadow of that ghastly messenger bending over the bed.

Whether it was some dreadful but wordless sentence its breathless lips conveyed as it stood there, I know not; but for an instant the shadow of a claw-like hand, from which the third finger was missing, appeared extended over the doomed man’s head; and then, as the clock struck one clear silvery stroke,

it fell, and a wild shriek rang through the room—a death-shriek.

I am not given to fainting, but I certainly confess that the next ten minutes of my existence was a cold blank; and even when I did manage to stagger to my feet, I gazed round, vainly endeavouring to understand the chilly horror which still possessed me.

Thank God! the room was rid of that awful presence—I saw that; so, gulping down some wine, I lighted a wax-taper and staggered towards the bed. Ah, how I prayed that, after all, I might have been dreaming, and that my own excited imagination had but conjured up some hideous memory of the dissecting-room!

But one glance was sufficient to answer that.

No! The summons had indeed been given and answered.

I flashed the light over the dead face, swollen, convulsed still with the death-agony; but suddenly I shrank back.

Even as I gazed, the expression of the face seemed to change: the blackness faded into a deathly whiteness; the convulsed features relaxed, and, even as if the victim of that dread apparition still lived, a sad solemn smile stole over the pale lips.

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories

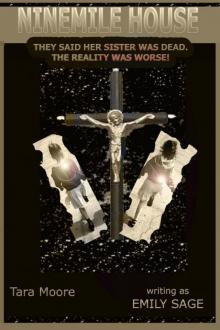

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Ninemile House

Ninemile House