- Home

- Tara Moore

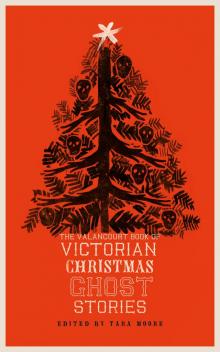

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Page 25

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Read online

Page 25

I cannot describe the extraordinary effect. If it had been dark it would have been altogether different. The brightness, the life around, the absence of all that one associates with the supernatural, produced a thrill of emotion to which I can give no name. It was not fear; yet my heart beat as it had never in any dangerous emergency (and I have passed through some that were exciting enough) beat before. It was simple excitement, I suppose; and in the commotion of my mind I instinctively changed the pronoun which I had hitherto used, and asked myself, would she come back? She did, passing me once more, with the same movement of the air (or so I thought). But by that time my pulses were all clanging in my ears, and perhaps the sense itself became confused with listening. I turned and walked precipitately away, descending the little slope and losing myself in the shrubberies which were beneath the range of the low sun, now almost set, and felt dank and cold in the contrast. It was something like plunging into a bath of cold air after the warmth and glory above.

It was in this way that my first experience ended. Miss Campbell looked at me a little curiously with a half-smile when I joined the party at the lochside. She divined where I had been, and perhaps something of the agitation I felt, but she took no further notice; and as I was in time to find a place in the boat, where she had established herself with the children, I lost nothing by my meeting with the mysterious passenger in the Lady’s Walk.

I did not go near the place for some days afterwards, but I cannot say that it was ever long out of my thoughts. I had long arguments with myself on the subject, representing to myself that I had heard the sound before hearing the superstition, and then had found no difficulty in believing that it was the sound of some passenger on an adjacent path, perhaps invisible from the Walk. I had not been able to find that path, but still it might exist at some angle which, according to the natural law of the transmission of sounds—Bah! what jargon this was! Had I not heard her turn, felt her pass me, watched her coming back? And then I paused with a loud burst of laughter at myself. “Ass! you never had any of these sensations before you heard the story,” I said. And that was true; but I heard the steps before I heard the story; and, now I think of it, was much startled by them, and set my mind to work to account for them, as you know. “And what evidence have you that the first interpretation was not the right one?” myself asked me with scorn; upon which question I turned my back with a hopeless contempt of the pertinacity of that other person who has always so many objections to make. Interpretation! could any interpretation ever do away with the effect upon my actual senses of that invisible passer-by? But the most disagreeable effect was this, that I could not shut out from my mind the expectation of hearing those same steps in the gallery outside my door at night. It was a long gallery running the full length of the wing, highly polished and somewhat slippery, a place in which any sound was important. I never went along to my room without a feeling that at any moment I might hear those steps behind me, or after I had closed my door might be conscious of them passing. I never did so, but neither have I ever got free of the thought.

A few days after, however, another incident occurred that drove the Lady’s Walk and its invisible visitor out of my mind. We were all returning home in the long northern twilight from a mountain expedition. How it was that I was the last to return I do not exactly recollect. I think Miss Campbell had forgotten to give some directions to the coachman’s wife at the lodge, which I volunteered to carry for her. My nearest way back would have been through the Lady’s Walk, had not some sort of doubtful feeling restrained me from taking it. Though I have said and felt that the effect of these mysterious footsteps was enhanced by the full daylight, still I had a sort of natural reluctance to put myself in the way of encountering them when the darkness began to fall. I preferred the shrubberies, though they were darker and less attractive. As I came out of their shade, however, some one whom I had never seen before—a lady—met me, coming apparently from the house. It was almost dark, and what little light there was was behind her, so that I could not distinguish her features. She was tall and slight, and wrapped apparently in a long cloak, a dress usual enough in those rainy regions. I think, too, that her veil was over her face. The way in which she approached made it apparent that she was going to speak to me, which surprised me a little, though there was nothing extraordinary in it, for of course by this time all the neighbourhood knew who I was and that I was a visitor at Ellermore. There was a little air of timidity and hesitation about her as she came forward, from which I supposed that my sudden appearance startled her a little, and yet was welcome as an unexpected way of getting something done that she wanted. Tant de choses en un mot, you will say—nay, without a word—and yet it was quite true. She came up to me quickly as soon as she had made up her mind. Her voice was very soft, but very peculiar, with a sort of far-away sound as if the veil or evening air interposed a visionary distance between her and me. “If you are a friend to the Campbells,” she said, “will you tell them——” then paused a little and seemed to look at me with eyes that shone dimly through the shadows like stars in a misty sky.

“I am a warm friend to the Campbells; I am living there,” I said.

“Will you tell them—the father and Charlotte—that Colin is in great trouble and temptation, and that if they would save him they should lose no time?”

“Colin!” I said, startled; then, after a moment, “Pardon me, this is an uncomfortable message to entrust to a stranger. Is he ill? I am very sorry, but don’t let me make them anxious without reason. What is the matter? He was all right when they last heard——”

“It is not without reason,” she said; “I must not say more. Tell them just this—in great trouble and temptation. They may perhaps save him yet if they lose no time.”

“But stop,” I said, for she seemed about to pass on. “If I am to say this there must be something more. May I ask who it is that sends the message? They will ask me, of course. And what is wrong?”

She seemed to wring her hands under her cloak, and looked at me with an attitude and gesture of supplication. “In great trouble,” she said, “in great trouble! and tempted beyond his strength. And not such as I can help. Tell them, if you wish well to the Campbells. I must not say more.”

And, notwithstanding all that I could say, she left me so, with a wave of her hand, disappearing among the dark bushes. It may be supposed that this was no agreeable charge to give to a guest, one who owed nothing but pleasure and kindness to the Campbells, but had no acquaintance beyond the surface with their concerns. They were, it is true, very free in speech, and seemed to have as little dessous des cartes in their life and affairs as could be imagined. But Colin was the one who was spoken of less freely than any other in the family. He had been expected several times since I came, but had never appeared. It seemed that he had a way of postponing his arrival, and “of course,” it was said in the family, never came when he was expected. I had wondered more than once at the testy tone in which the old gentleman spoke of him sometimes, and the line of covert defence always adopted by Charlotte. To be sure he was the eldest, and might naturally assume a more entire independence of action than the other young men, who were yet scarcely beyond the time of pupilage and in their father’s house.

But from this as well as from the still more natural and apparent reason that to bring them bad news of any kind was most disagreeable and inappropriate on my part, the commission I had so strangely received hung very heavily upon me. I turned it over in my mind as I dressed for dinner (we had been out all day, and dinner was much later than usual in consequence) with great perplexity and distress. Was I bound to give a message forced upon me in such a way? If the lady had news of any importance to give, why did she turn away from the house, where she could have communicated it at once, and confide it to a stranger? On the other hand, should I be justified in keeping back anything that might be of so much importance to them? It might perhaps be something for which she did not wish to give her authority. Sometime

s people in such circumstances will even condescend to write an anonymous letter to give the warning they think necessary, without betraying to the victims of misfortune that anyone whom they know is acquainted with it. Here was a justification for the strange step she had taken. It might be done in the utmost kindness to them, if not to me; and what if there might be some real danger afloat and Colin be in peril, as she said? I thought over these things anxiously before I went downstairs, but even to the moment of entering that bright and genial drawing-room, so full of animated faces and cheerful talk, I had not made up my mind what I should do. When we returned to it after dinner I was still uncertain. It was late, and the children had been sent to bed. The boys went round to the stables to see that the horses were not the worse for their day’s work. Mr. Campbell retired to his library. For a little while I was left alone, a thing that very rarely happened. Presently Miss Campbell came downstairs from the children’s rooms, with that air about her of rest and sweetness, like a reflection of the little prayers she has been hearing and the infant repose which she has left, which hangs about a young mother when she has disposed her babies to sleep. Charlotte, by her right of being no mother, but only a voluntary mother by deputy, had a still more tender light about her in the sweetness of this duty which God and her goodwill, not simple nature, had put upon her. She came softly into the room with her shining countenance. “Are you alone, Mr. Temple?” she said with a little surprise. “How rude of those boys to leave you,” and came and drew her chair towards the table where I was, in the kindness of her heart.

“I am very glad they have left me if I may have a little talk with you,” I said; and then before I knew I had told her. She was the kind of woman to whom it is a relief to tell whatever may be on your heart. The fact that my commission was to her, had really less force with me in telling it, than the ease to myself. She, however, was very much surprised and disturbed. “Colin in trouble? Oh, that might very well be,” she said, then stopped herself. “You are his friend,” she said; “you will not misunderstand me, Mr. Temple. He is very independent, and not so open as the rest of us. That is nothing against him. We are all rather given to talking; we keep nothing to ourselves—except Colin. And then he is more away than the rest.” The first necessity in her mind seemed to be this, of defending the absent. Then came the question, From whom could the warning be? Charley came in at this moment, and she called him to her eagerly. “Here is a very strange thing happened. Somebody came up to Mr. Temple in the shrubbery and told him to tell us that Colin was in trouble.”

“Colin!” I could see that Charley was, as Charlotte had been, more distressed than surprised. “When did you hear from him last?” he said.

“On Monday; but the strange thing is, who could it be that sent such a message? You said a lady, Mr. Temple?”

“What like was she?” said Charley.

Then I described as well as I could. “She was tall and very slight; wrapped up in a cloak, so that I could not make out much, and her veil down. And it was almost dark.”

“It is clear she did not want to be recognised,” Charley said.

“There was something peculiar about her voice, but I really cannot describe it, a strange tone unlike anything——”

“Marion Gray has a peculiar voice; she is tall and slight. But what could she know about Colin?”

“I will tell you who is more likely,” cried Charley, “and that is Susie Cameron. Her brother is in London now; they may have heard from him.”

“Oh! Heaven forbid! oh! Heaven forbid! the Camerons of all people!” Charlotte cried, wringing her hands. The action struck me as so like that of the veiled stranger that it gave me a curious shock. I had not time to follow out the vague, strange suggestion that it seemed to breathe into my mind, but the sensation was as if I had suddenly, groping, come upon some one in the dark.

“Whoever it was,” I said, “she was not indifferent, but full of concern and interest——”

“Susie would be that,” Charley said, looking significantly at his sister, who rose from her chair in great distress.

“I would telegraph to him at once,” she said, “but it is too late to-night.”

“And what good would it do to telegraph? If he is in trouble it would be no help to him.”

“But what can I do? what else can I do?” she cried. I had plunged them into sudden misery, and could only look on now as an anxious but helpless spectator, feeling at the same time as if I had intruded myself upon a family affliction: for it was evident that they were not at all unprepared for “trouble” to Colin. I felt my position very embarrassing, and rose to go away.

“I feel miserably guilty,” I said, “as if I had been the bearer of bad news; but I am sure you will believe that I would not for anything in the world intrude upon——”

Charlotte paused to give me a pale sort of smile, and pointed to the chair I had left. “No, no,” she said, “don’t go away, Mr. Temple. We do not conceal from you that we are anxious—that we were anxious even before—but don’t go away. I don’t think I will tell my father, Charley. It would break his rest. Let him have his night’s rest whatever happens; and there is nothing to be done to-night——”

“We will see what the post brings to-morrow,” Charley said.

And then the consultation ended abruptly by the sudden entrance of the boys, bringing a gust of fresh night air with them. The horses were not a preen the worse though they had been out all day; even old grumbling Geordie, the coachman, had not a word to say. “You may have them again to-morrow, Chatty, if you like,” said Tom. She had sat down to her work, and met their eyes with an unruffled countenance. “I hope I am not so unreasonable,” she said with her tranquil looks; only I could see a little tremor in her hand as she stooped over the socks she was knitting. She laid down her work after a while, and went to the piano and played accompaniments, while first Jack and then Tom sang. She did it without any appearance of effort, yielding to all the wishes of the youngsters, while I looked on wondering, How can women do this sort of thing? It is more than one can divine.

Next morning Mr. Campbell asked “by the bye,” but with a pucker in his forehead, which, being now enlightened on the subject, I could understand, if there was any letter from Colin? “No,” Charlotte said (who for her part had turned over all her letters with a swift, anxious scrutiny). “But that is nothing,” she said, “for we heard on Monday.” The old gentleman uttered an “Umph!” of displeasure. “Tell him I think it a great want in manners that he is not here to receive Mr. Temple.” “Oh, father, Mr. Temple understands,” cried Charlotte; and she turned upon me those mild eyes, in which there was now a look that went to my heart, an appeal at once to my sympathy and my forbearance, bidding me not to ask, not to speak, yet to feel with her all the same. If she could have known the rush of answering feeling with which my heart replied! but I had to be careful not even to look too much knowledge, too much sympathy.

After this two days passed without any incident. What letters were sent, or other communications, to Colin I could not tell. They were great people for the telegraph and flashed messages about continually. There was a telegraph station in the little village, which had been very surprising to me at first, but I no longer wondered, seeing their perpetual use of it. People who have to do with business, with great “works” to manage, get into the way more easily than we others. But either no answer or nothing of a satisfactory character was obtained, for I was told no more. The second evening was Sunday, and I was returning alone from a ramble down the glen. It was Mr. Campbell’s custom to read a sermon on Sunday evenings to his household, and as I had, in conformity to the custom of the family, already heard two, I had deserted on this occasion, and chosen the freedom and quiet of a rural walk instead. It was a cloudy evening, and there had been rain. The clouds hung low on the hills, and half the surrounding peaks had retired altogether into the mist. I had scarcely set foot within the gates when I met once more the lady whose message had brought so

much pain. The trees arched over the approach at this spot, and even in full daylight it was in deep shade. Now in the evening dimness it was dark as night. I could see little more than the slim straight figure, the sudden perception of which gave me—I could scarcely tell why—a curious thrill of something like fear. She came hurriedly towards me, an outline, nothing more, until the same peculiar voice, sweet but shrill, broke the silence. “Did you tell them?” she said.

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories

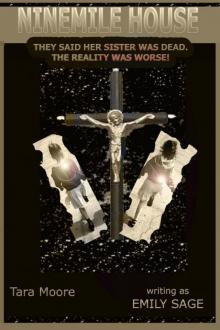

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Ninemile House

Ninemile House