- Home

- Tara Moore

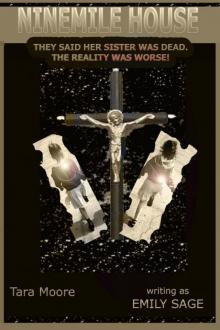

Ninemile House Page 24

Ninemile House Read online

Page 24

CHAPTER 24

Gabby took a deep breath and stepped onto the bus. After showing her ticket to the driver, she went upstairs and found a seat at the very front where she had a bird’s eye view. These days she took the bus almost as a matter of routine, but today she was travelling further than she ever had before, a whole lot further. Slightly dizzy at her own daring, she worried what Derry would say when she found out. Would she be angry? Upset? Probably both, she admitted to herself. She would in her place. If the boot was on the other foot, she would probably shout and call Derry selfish, maybe even tell her never to darken her door again. But, selfish or not, this was something Gabby had to do, for everyone’s sake. Sitting back, she let her eyes drift out the window, more used now to the teeming masses of people thronging the pavements and shops, the constant barrage of noise from the traffic, the incessant, invasive neon lights flashing on an off, even in daylight. She was more used to them, but she still didn’t feel comfortable, still didn’t feel as if she fitted in. To the ordinary man in the street, there was nothing to single her out from anyone else. With her new clothes and make-up and her hair almost as shiny and soft as Derry’s, she looked the part now. Looked normal. On the inside though, in her heart and in her soul where it counted, she felt different, a fish out of water, nagged by the feeling that at any moment someone would point the finger and unmask her for the impostor she was.

When the bus pulled up outside the Gresham Hotel in O’Connell Street, Gabby transferred straight onto another one, a coach this time, marvelling at how smoothly it had all gone so far. At ten a.m. it was still early and, traffic permitting, the driver told her, in a soft Tipperary accent, she would be at her destination in approximately two and a half hours. Gabby found herself a seat at the back of the bus and sat down. Only when the engine started up and the bus pulled slowly out into the traffic did she become aware that her heart was pounding in her ears and that her hands had started to shake.

With an effort, she willed herself to stay calm. She was here of her own volition. No one had forced her to go. Nobody even knew, apart from Mahendra who had plotted the details of the journey for her. Poor Mahendra. There was an ache in her heart when she thought of him. How sad he had looked, when she told him her plans, those spaniel-dark eyes of his filling with tears, sparkling like diamonds on a velvet background. But in his wisdom he had understood that this was her destiny and when she walked away leaving him on the beach, his dark hair tousled by a teasing breeze, one hand half-lifted as if he would stop her, it was all she could do to prevent herself from running back to him, from flinging herself into his arms and accepting what he had to offer. But to do that would have been to destroy him. Like the beautiful Lotus flower of his native land needed water in which to blossom and grow, Mahendra needed love. Gabby couldn’t love him. She was arid and dry, a fifteen-year-old emotional cripple in a middle-aged body.

Now as black and white signposts flagged up unfamiliar towns, Kilcullen, Athy, Ballylynan, she remembered his last words to her, an old Chinese proverb, he said, cradling her face between his strong brown hands. “If you love something, you must let it go free. If it comes back, it is yours forever. If it does not, it never was.” He’d kissed her then, paternal kisses almost, dropping one on her forehead, one on the tip of her nose, one on her lips, lightly, undemanding, lovingly. “You, little bird, were never mine. Fly free. Go find your destiny.”

As the bus drove inevitably onwards, the towns gave way to fields and trees, passed through little villages where flat-capped men, taking a break from their work, leaned against the walls of public houses, some with pint glasses in their hands chatting and watching the world go by. Women with bags of shopping or trailing children by the hand walked purposefully up and down the streets or disappeared into houses or shops and more than once the bus slowed to let a tractor squeeze past on the opposite side of the road, or to let a herd of mournful-eyed cattle pass by. The black and white ones, Gabby recalled from her childhood, were Friesians and the red-coated ones with the white heads were Herefords. The black one with a fringe of curls on its forehead and a ring through its nose was a bull. She knew that because she had been chased by one once – once long ago, so long ago, that now she wondered if she had actually imagined it. Maybe it had never actually happened at all or maybe it had happened to someone else and she remembered it as happening to her. Lately, she wasn’t even sure where she actually ended and other people began. She felt formless, a wisp of smoke, bending and blending, shaping and being shaped to fit the contours of a world in which more and more she had come to believe, she had no place. She was Cinderella’s ugly sister. The shoe would never fit. She had to go back.

Now and again the bus stopped and people got on or off, all mercifully absorbed in their own business and with no interest whatsoever in the plainly dressed woman crying quietly at the back of the bus.

Castlecomer flashed past in a blur of grey streets and houses, past an old cinema, bearing the sign Meally Auctioneers, past the Glanbia Creamery with its ugly metallic vats pointing at the sky, and then they were out of Castlecomer and heading towards Callan. Gabby sat up straighter in her seat and stared expectantly out the window. Any moment now. Any moment and she would see Slievenamon, The Mountain of the Women, crowning purple in the distance, a shy Venus, reluctant to disrobe from its modest drapery of wispy clouds.

“Next stop, Ninemilehouse,” called the driver, his eyes in the mirror meeting hers from all the way down the length of the bus. He knew what she was, Gabby thought. The impostor was unmasked. Like the mark of Cain, the mark of the nuns was on her still and no amount of perfume, powder, paint or expensive clothes would ever take it away.

If it comes back, it’s yours forever, Gabby thought, dragging her suitcase up along the gravelled drive to Ninemilehouse. She had come back. Forever!

“Ah, Gabby,” Sr Peter looked triumphant. “The Prodigal returns. I wondered how long it would take.”

In the time she had been away, Gabby was surprised to see that the nun appeared to have shrunk and as a consequence wasn’t half so frightening. Her power had diminished in direct proportion to her height. Age had withered her. Time and distance had put her in perspective. Placing her suitcase on the floor, Gabby drew herself up to her full height.

“My name,” she said quietly and with dignity, “is Theresa”.

***

“Angie. Angie, please won’t you talk to me.” Theresa stood looking helplessly at her friend as she gazed out the window, her back rigid with anger, tension evident in every line of her half-emaciated body. “Oh, please.”

Angie spun round suddenly, her eyes ablaze with anger and something else, hurt and betrayal. “And why the bloody hell should I, Gabby? You didn’t want much of my talk when you buggered off to stay with that posh sister of yours. You didn’t want to know me, then, did you? But now that it’s all gone pear-shaped and you’re back, you expect me to jump to your tune. Just like that!”

“I did write to you,” Theresa protested. “I wrote to you, loads of letters, but you never replied and I was really worried about you.”

“Sure you were!” Angie snorted, tossing her red hair, but she started to look a little less sure of her ground. “And when did you send these precious letters, may I ask?”

“Every other week. Honestly, Ange. I didn’t forget you. I could never forget you. You’re one of the main reasons I came back. I missed you so much.”

“You must be mad!” Angie said, but there were tears glimmering in her eyes and in another moment she was hugging Theresa for all she was worth. “Oh, God, I missed you too. That old bitch, Sr Peter, took everything she possible could out on me. Talk about wee slavey. It’s a miracle I’m still alive.” Her face darkened, as the penny suddenly dropped. “She’s got them, the letters. I’ll bet you any money you like, the bloody rip has taken them. Well, by God, she’d better give them back, because if she doesn’t I won’t be responsible for what I do to her, nun or no bloody nun!”

/>

“She wouldn’t do that!” Shocked, Theresa looked uncertainly at the other woman. “Would she?”

“Jesus, the naivety of you.” Amazed, Angela shook her head from side to side. “Sr Peter, let me remind you is the same old bitch that gave us hell all these years. Remember the beatings. Remember the bone-crushing weariness after she made us work like slaves. Remember the way she snatched infants from their mothers and slapped the mothers when they protested. And you honestly think she wouldn’t meddle with my post? God, they broke the mould when they made you, all right.” With a determined frown, Angela strode towards the door.

“Where are you going?” Theresa looked scared.

“To get my bloody letters back, of course. And if she doesn’t give them to me, I’ll swing for her, so help me God.”

“Who are you going to swing for, Angie?” Old Mary poked her head round the door, coming in on the end of the conversation.

“Who are you going to swing for, Angie?” Clare, the echo, was directly behind her.

“Sr Peter!” Angie snapped, pushing past the two old women and taking the steps downstairs two at a time, such was her towering rage.

“Stop her, Gabby!” Alarmed, Mary’s hand flew to her mouth.

Clare’s hand followed suit. “Stop her, Gabby!”

Exasperated and worried about Angie, Theresa rounded on the old women. “Would you two ever stop calling me, Gabby. I’m Theresa now. T-h-e-r-e-s-a!”

“She’s Theresa now,” Mary told Clare, who told her right back.

“She’s Theresa now.” For a moment, Clare looked confused, then she smiled slowly as a memory long dead and buried surfaced in a moment of clarity. “She’s Theresa and I’m Bernadette. Bernadette O’Hanrahan, from Kiltimagh, County Cavan.”

Mary exchanged disbelieving looks with Derry. Her eyes filled with tears. “Oh, Clare, you remembered.”

“Oh, Clare, you remembered.” As quickly as it had parted the veil came down again, and Bernadette O’Hanrahan, was once more wrapped once more in the madness of Ninemilehouse.

EPILOGUE

Theresa was cleaning her bedroom window, polishing it to a shine with vinegar and newspaper. In the distance, Slievenamon stood bathed in rosy evening light, its every curve and shadow familiar to her as her own face. Nowadays, accompanied by Angie, she often climbed it, the pair of them sitting at the top and talking about how much their lives had changed. For the better! No longer prisoners, they were free to come and go from Ninemilehouse, as they pleased. That they chose to stay at all was a mystery to all but themselves.

In the background Angie and old Mary were bickering good naturedly and

Theresa was pleased to hear Mary laugh, something she did infrequently now that poor old Clare had died. But she wasn’t called Clare on her headstone. Theresa had insisted on that. She was Bernadette O’Hanrahan, late of Kiltimagh, County Cavan. Derry had paid for the gravestone. Theresa frowned as she recalled how upset Derry at been at what she termed her defection back to the convent, but eventually she had come to understand a little better and now she, James, with whom she appeared to have sorted out whatever differences they’d been having, thank God, the twins and Sheila, of course, visited often and sometimes Theresa went to stay with them. But never for long. The outside world was still too frightening. She didn’t see Michael though, or Mahendra. Romantic love wasn’t for her. She accepted that. Besides she was as close to happy now as she had ever been.

She rubbed at a particularly stubborn mark on the window pane, pausing as a taxi drove in through the gates and pulled up on the drive just below. Curious, she watched as the passenger door opened and a tall, dark-haired priest climbed out. He stood for a moment, getting the measure of the place, his gaze sweeping over the dark forbidding walls and then his eyes met hers through the glass and he smiled. Fumbling at the latch, she opened the window and leaned out.

“Can I help you, Father?”

“I hope so.” His accent was American. “I’m looking for my mother. Maybe you know her, Theresa McManus.”

“Michael?” Theresa’s hand flew to her heart. Her voice was a whisper, a breath, a prayer. “Michael, is that you?”

###

If you enjoyed this book, why not check out RSVP and Blue-Eyed Girl. Available from all good book stores and online retailers. Or, why not visit my website , or connect with me on Twitter and Facebook

153

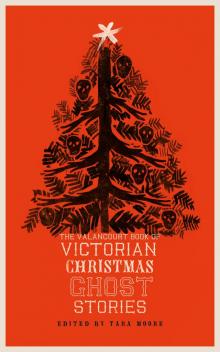

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Ninemile House

Ninemile House