- Home

- Tara Moore

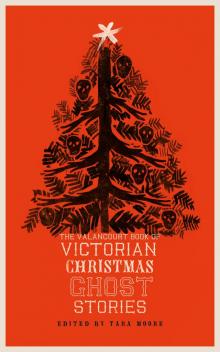

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Page 18

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Read online

Page 18

When, some quarter of an hour after, Philip Carlyon followed his friend to the room he had made over to him for the night, he found Jack still dressed, seated upon the bed-side, one of the dreariest objects he had ever had the misfortune to gaze upon.

“Come, Jack,” cried he cheerily, “aren’t you going to bed to-night?”

But Jack was not to be cheered.

“Bed!” groaned the wretched young fellow; “what’s the good of bed, or anything else? I wish I was dead and buried.”

“I daresay you’ll be accommodated some day; so don’t let that distress you, unless you are in a very particular hurry and can’t afford to wait.”

“O Phil, old man, don’t chaff a fellow! I verily believe I’m the most miserable dog alive.”

“It’s well Miss Dormer does not hear you!” laughed the unsympathising Phil.

“Don’t mention her!” cried Jack, with a genuine shiver.

“I’ll tell you what it is, Jack,” said Philip, seating himself by his friend’s side; “if you’ll go to bed like a Christian, instead of sitting groaning there like an old woman at a prayer-meeting, I’ll do what I can to get you out of this hobble; and I think I see a way. But if you don’t—by Jove!” cried Philip threateningly, “the little governess shall marry you to-morrow if she likes. So now, good-night.”

Jack, another man in these last few seconds, started up.

“Do you really mean it, though? I’ll bless you for ever and a day!”

“You turn-in, then,” said Phil.

“All right!” said Jack; and Philip actually heard him whistling as he went his way to Jack’s late bedroom.

Here it appeared that our friend had taken care to provide himself with the various trifling necessaries for a comfortable night—for it was not his intention either to go to bed or to sleep, as you may suppose. His first move was to lock the door; having done which, he discovered with a smile that the key was brought into such a position that another applied from without would send it out softly upon the mat beneath. So far so good. Philip then doctored the fire, exchanged his coat for the more luxuriant folds of the most inviting of dressing-gowns, and lastly, after mixing himself a glass of something steaming and fragrant enough to have tempted even a ghost itself to become for the time mortal, sat himself down in his easy-chair, and with slippered feet upon the fender, set himself to read. Twelve, one, two, from the clock on the landing outside, and still Mr. Carlyon read on. Three. Mr. Carlyon closed his book, and seemed to listen. There was some little life in the fire still, and this he left burning. The candles he carefully extinguished; and then stretched himself upon the bed. It was not too soon; there was the the soft opening of a distant door, a scarcely audible footstep creeping cautiously towards his own, a halt on the mat outside, a moment’s breathing space. Then the key that was within the room fell, not noisily, but dulled by the soft carpeting, the lock was turned, the door crept slowly open, and then—enter ghost! Philip, waiting expectant as he was, felt himself giving an involuntary shiver. Prepared even to get some enjoyment out of the affair, Phil felt that he could for the moment realise just a something of what poor Jack’s feelings had been. But it must be allowed that this was only for a moment. With a smile that surely meant mischief, could the poor ghost but have seen it, Philip followed with his half-closed eyes the white-draperied one’s progress until the position between the window and the bed was gained. Yes, there it stood, just as Jack had described it; not tall certainly, but ghostly enough for twenty ghosts.

“Now for act the second,” said Phil to himself.

Act the second commenced by the utterance of Jack Layford’s name twice, thrice it may be, in the most sepulchral tones of which a rather soprano voice is capable. At the third call, the occupant of the bed showed signs of consciousness, as it was evidently necessary he should do if the play was to be properly carried out.

As Philip had calculated, the cue was taken. It was probably much the same oration as that to which the room’s owner of the previous night had been treated, and Philip Carlyon heard it politely to the end.

Suddenly through the room there rang a stifled cry, almost shriek, but it certainly did not proceed from Mr. Carlyon. That gentleman—polite, smiling—stood, one hand upon the fast-closed door, the other waving a courteous adieu to poor Jack’s terror, now white, appealing, frantic, all but at his feet. Her retreat thus cut off, Miss Dormer—for of course it was she—as the only thing left her to do, was down on her knees, imploring piteously for mercy at her captor’s hands. Alas, poor ghost! There was not much pretence of disguise or concealment now; the time for that was past.

“I will promise anything,” groaned the wretched little woman, “only let me go, dear Mr. Carlyon! I will leave the house to-morrow—to-night! I will never see John Layford again! Only let me go!”

Mr. Carlyon was not so terrible as he looked—and the firelight showed him awfully dark and stern to the miserable woman at his feet. “Get up, Miss Dormer!” he said authoritatively. “Don’t kneel there! You shall go, on your own terms—that is, you leave this place at once, and never see my friend Jack again. The Squire must of course know all; but it shall go no further. And now go.”

So, defeated, humbled, almost pitiable in her humiliation, the poor plotter slunk out.

“Check, I think,” said Phil, with a grim smile, as he once more closed the door, not taking the trouble this time to lock it.

And now what more is there to tell? At the breakfast-table that morning there was no Miss Dormer, but there was a clamour and babel of voices quite beyond all the endeavours of Flop to still; and when the two little robins came to be informed, in answer to their wondering inquiries, that Miss Dormer would be no more seen by them on that, or indeed any other, morning, however future, the tumult was redoubled. Little Tiny, for her part, at once arriving at the melancholy conclusion of Miss Dormer’s having unexpectedly deceased during the night—after the manner of a favourite canary about a month since—commenced a tributary howl to the memory of the departed, but suddenly stopped short—moved, possibly, by some flash of consolation concerning lessons that would not have to be said; and, changing her small mind altogether upon the subject, laughed instead, greatly to the comfort of all parties.

“That’s right,” cried Flop approvingly. “Of course we are all very sorry; but we aren’t going to cry, are we, Jack?”

Jack, very red, mumbled something about “girls” and “nonsense;” and Philip and Margaret were fain to hide their heads behind the great silver tea-urn.

After breakfast, and when the two were standing alone by the dining-room fire, talking together in the low-voiced happy way peculiar to young people in their situation, Jack came in equipped for a journey. There was a certain sad look in the young fellow’s eyes as they fell upon the two, but he went bravely up to where they stood and put out his hand. “Good-bye, Margey,” he said; “and good-bye to you, too, old fellow. I’m going back to town; but you needn’t follow yet. I shall be down at Easter, Meg; and I suppose,” said Jack, with a little smile, and laying a kindly hand on Phil Carlyon’s shoulder, “that I may bring with me the best friend I ever had.”

L. N.

HOW PETER PARLEY LAID A GHOST

A STORY OF OWLS’ ABBEY

Peter Parley was a transatlantic, unprotected brand. The original idea for nourishing writing for children came from an American, Samuel Goodrich. His brand of common-sense, educational fare became so popular that imitators adopted his style, and his pseudonym. William Martin, a British editor, published Peter Parley’s Magazine from 1839 to 1863. While it was in operation, the magazine put out a Christmas annual, and this tradition continued even after the magazine itself had been discontinued. This annual endeavor appeared each Christmas season from 1840 to 1892, and, with colored plates after 1845, it sold very well as a Christmas and New Year’s gift.7 The story here (first published in 1875) represents a wealth of similar ghost stories intended for Christmas reading in that it see

ks to build tension while teaching a lesson about the reality of ghosts.

7 Carol A. Bock, “Peter Parley’s Magazine” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature. Edited by Jack Zipes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

I know it has been the habit of young people to speak of me and think of me as having been always an old man. Certainly, since I began to talk to my young friends, I have got considerably older than I was when I first introduced myself to them. But I have been a boy like themselves for all that, and I still appreciate and sympathise with all the delights and sorrows of boyhood and girlhood; with an exception, however; I do not appreciate and sympathise with delights or sorrows which have cruelty, falsehood, or indeed any vice as their cause or consequence. Some follies, also, I am fain to overlook; but folly which endangers life, or places people in peril which would not otherwise approach them, or folly which believes not in the sufferings of others I am very severe upon. Practical joking, a very common and often a very fatal folly, is my special abhorrence. As a boy, I was not cleverer nor more book-learned, nor more perfect than my contemporaries, nor than my present reader perhaps; but I kept myself clear, either by inclination or by force of advice, from certain follies which I now undertake to reprehend. I hope I have been just, during these many years; for I have never rebuked boys for faults which I was partial to in my early youth.

All this is vastly dry, you’ll say; and more like Peter Prosy than Peter Parley; but I never begin a story wherein I have been myself concerned without telling my young friends that I don’t profess to have been the perfection of boyhood, but that I vividly remember my youth, and am, as far as kindliness to youth is concerned, and thorough sympathy with its pleasures and pains, a boy in heart still. Now, having said my prefatory say, I will go on to relate a little adventure which befell me some—well, never mind how many—years ago.

Near the village where I was born there used to stand the remains of an old Gothic abbey, formerly dedicated, I believe, to some saint, by name Olaus. In mediæval times this name was all very well, but as centuries crept on, so fell away the appellation, as the stones of the abbey themselves; and St. Olaus’ Abbey was speedily corrupted into St. Owls’, and, finally, into Owls’ Abbey. Perhaps the advanced state of decay in which this old ruin was in my day had helped to favour this title, for Owls’ Abbey deserved its name on account of the thousands of night-birds which infested and built in it. At the time of which I write some respectable vestiges still remained of the old pile; a broken arch, a crumbling window, and so on. And I will take this opportunity of instructing my young friends in some of the points whereby they will in future be able to distinguish Gothic from Norman ruins.

I often hear youths, otherwise well-informed, commit sad blunders in their wild guesses at the different styles of architecture, so I will briefly tell them how to avoid such exposures of ignorance for the rest of their lives. Gothic architecture is often called—and very properly—“Pointed architecture;” this one name will help as a guide; for by the term “Gothic” we understand that style wherein the pointed arch as applied to various purposes of construction becomes a leading characteristic of the edifice. This sort of pointed architecture dates from the rise of Christianity itself, and was probably devised in opposition to the Pagan form of building. Some say that an avenue of overbranching trees was the object which suggested the Gothic arch; but though authorities are not agreed upon its origin, it is sufficient to remember that Gothic architecture is pointed; while Norman architecture has round arches.

The splendid aisles of Westminster Abbey are almost unequalled as specimens of pointed arches; and you will know now that they are Gothic. Specimens of Norman arches you will find in Waltham Abbey, and, nearer home, at at Saint Bartholomew’s Church, West Smithfield; and these are in contradistinction round. There are many sub-divisions of both Gothic and Norman, of course, but I have merely laid down the broad lines by which you will be able to decide on the architecture of this sort of ruin whenever you meet with it, in your rambles or at pic-nics.

Owls’ Abbey, then, was an old Gothic ruin; standing at the foot of a pleasant green hill, and embosomed in fine trees, it was a picturesque spot, and used to attract many visitors, pedestrian tourists, and even our own village folk; who would frequently take an al-fresco dinner within the old grey walls, while summer time and daylight lasted. While there was bright sun to light up the dark ivy and keep the bats and owls in their hiding places, such pic-nics were not rare. Nutting parties would often wander amidst the ruins, and adventurous seekers of nests, and trappers of rats and rabbits, penetrated the dim recesses of Owls’ Abbey at just periods of the year. But when winter stripped the fading trees, and beneath the cold winter’s moon the ruins looked ghastly white, and skeleton-like in their leaflessness, there was no villager hardy enough to venture even at sunset into the dismal abbey; and as to passing through it by night, though the “short cut” to many places lay thereby, that was out of the question. And why, do you suppose? Because the simple villagers would have it that the abbey was haunted.

Superstition is almost invariably the result of the want of education; or, in plain English, the ignorant are almost always credulous. You will readily understand this by referring to many wonderful appliances of this day; such as gas, steam, electricity as applied to telegraphs, and so on; the which, if discovered only a hundred years ago would certainly have brought their inventors to the stake as sorcerers. Yet the world, better informed in these times, regards such men as benefactors to their country and to the world.

The old belief in ghosts, goblins, sprites, and elves has helped to produce some very pretty poetry, but beyond this I cannot possibly see what gain there could be out of such folly. In these days, when science shows us what ghosts and apparitions really are; namely, creations of a disordered body, or disordered mind, we seldom come across a haunted house in cities. In villages, however, where education grows but slowly, you will generally find some spot supposed to be frequented by spirits, and discover amongst the less-informed folk a tendency to accept any foolish tale of hobgoblins as serious truth. I don’t believe that any of my readers are so silly as to feel alarm at passing through dim and silent places by night; they have advantages now which make my belief in their good sense quite secure.

The foolish people of the village round and about Owls’ Abbey were firmly persuaded that the old ruin was haunted, by not only the traditional old abbot—who had been barbarously slain at the sacking of the abbey by Oliver Cromwell—but by a more modern apparition, reported to be the wraith of an unfortunate Irish pedler, who had been waylaid, robbed, and beaten to death by some desperadoes, for the sake of his few brooches, etc. This renowned spectre was called “Barney’s Ghost,” and there were not a few who could declare they had seen this ghost apparently hunting amongst the underwood of the abbey for the contents of his pack. Wonders did not cease here, for even the little white stone bridge which spanned the village stream hard by the valley wherein the abbey stood, had its mysterious visitor, in the impalpable person of a White Lady, who sat on the key-stone of the arch, engaged in the doleful but tidy duty of combing her long golden hair, for the better accomplishment of which occupation the lady carried her head in her lap. Altogether, Owls’ Abbey and its precincts supplied ample material for making the foolish villagers afraid of their own shadows. I was about fifteen when the events which I shall now relate took place.

One fine evening in summer-time, as I was returning from a day’s fishing in the mill-stream, about a mile from the village, I saw a lot of men talking earnestly to old Lapp, the cobbler, who was seated outside his little cottage, working in the cool of the day. I knew most of the men by sight, for the village was not a very extensive place. There were Joe Barratt, the blacksmith—his forge-fire was out for that evening; old Abel Tandy, who was supposed to be the oldest inhabitant, and lived very well on the strength of being too decrepit to work; Dick Millet, assistant at the flour factory; Jim Lantern, th

e town-crier, and others; but amongst them was a man whom I had never seen before, and who was evidently a traveller only passing through the village. He had, it seems, from the conversation which I overheard, been enquiring into the village news and the village “lions;” amongst which, you may be sure, Barney’s ghost, and the White Lady had been trotted out with great effect. The stranger had a smile on his face while old Lapp was holding forth.

“Never you mind, mister! I see it: that’s enough!’’

“Ah!” said the new comer, “what was it that you say you saw?”

“Say I saw?” retorted old Lapp. “I did see it. There was Barney’s ghost a-hunting about in the ferns for the lockets and chains as was dropped thereabouts; a white misty sort of figure; not of this world, I know, and I knew it at once for Barney’s spirit!”

“Ah!” chorussed the bystanders. “You’re right, old Lapp!”

“When was the said Barney murdered then?” enquired the stranger.

“Ask Abel Tandy,” said Barratt, in a solemn voice.

All eyes turned to the aged man, who, with considerable pride at such a recollection, replied, shrilly—“Eighty year ago, come Michaelmas!—eight-y year ago! I were a boy then, and had seen Barney ever so many times! Ay, ay! it’s all that time! Eight-y year!”

“Why, then,” said the traveller, turning to old Lapp, “you can’t be more than fifty-eight or so, and couldn’t have seen Barney alive. How did you manage to recognise him?”

“Hadn’t I been told that his spirit haunted the abbey, and was to be seen groping about for his jewellery? and when I see the figure a-doing so, wasn’t I right in supposing it were Barney’s ghost?”

“Ah! sure!” repeated the chorus, delighted to see the champion of the ghost in the ascendant.

“And you mean to tell me that this abbey is haunted?”

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories

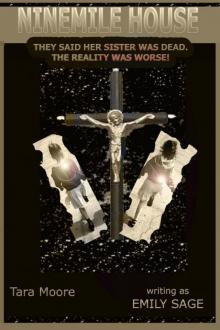

The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories Ninemile House

Ninemile House